by David Cesarani

Until the mass eviction of German Jews to Theresienstadt, the ghetto-camp had a predominantly Czech Jewish character. At the end of 1941 it accommodated 7,545 Jews from Prague and Brno. Over the next six months 26,524 Jews from all over Bohemia and Moravia were squeezed into the fortress. Between July and December 1942 the number of Czech Jewish arrivals doubled again, but during that time thousands were deported through what was in effect Theresienstadt’s revolving door. They were replaced by approximately 53,000 German and 13,000 Austrian Jews, although many of them, too, were removed to the east after only a few weeks or months. From mid-1942 the internal administration as well as the external appearance and ambiance of Theresienstadt changed to reflect the demographic transformation.

Helga Weiss and her family were among the first Prague Jewish families to be forcibly replanted. Within weeks of their arrival they suffered two shocks. First, on 9 January 1942, nine young men were hanged for the apparently trivial crime of attempting to smuggle letters out of the ghetto. This atrocity was followed by news that 1,000 inhabitants were to be transported to Riga. Helga expressed the general disillusionment when she reflected, ‘We thought at least now we’re in Terezin we’d be spared any more of this.’ Instead, from then on every day was lived under the threat of deportation. The terror of removal was juxtaposed with the pleasure of meeting friends and family as transports flooded in. There were so many reunions that Weiss remarked, ‘Prague has come . . .

The beginnings of Theresienstadt

Until mid-1942, the deported Jews shared the fortress town with its indigenous inhabitants. But whereas the Czechs lived in family houses, the Jews were separated by gender and packed into the original barracks and living quarters adapted from other installations. In the Sudeten barracks fifty men lived in each room, stacked in bunks; the women in the Magdeburg barracks had slightly more space. Girls stayed with their mothers and boys with their fathers until they reached the age of twelve when youths moved into children’s homes that offered more space, better facilities, and rooms for schooling. All adults except the old and the infirm were expected to join working parties, many of which operated outside the fortress walls. The ghetto was guarded by a detail of 120–150 Czech gendarmes. The Jews rarely saw a German.

During the Czech period, Eichmann and his deputy Siegfried Seidl, who was responsible for running the ghetto on a day-to-day basis, appointed Jacob Edelstein as the Elder, with Otto Zucker as his deputy. Both men were Zionists with years of public service behind them. They presided over a council of thirteen elders who supervised several departments covering administration, building and maintenance, finance, labor and economic matters, and public heath. An ‘Ordnungswache’, or Order Watch, patrolled the streets and escorted Jews in and out of the ghetto confines. Crucially, the internal administration was responsible for maintaining a registry of all the residents and selected who would leave when the Germans ordained a deportation. The actual deportation lists were compiled by the Transport Committee. Since it was always the target of intense lobbying, during the days and hours before a deportation an Appeals Committee examined claims for exemption.

Norbert Troller Redesigns Theresienstadt

On the surface, the categories were clearly set out by the Germans in guidelines issued to the council on 5 March 1942. Families with young children were not to be broken up. Men with decorations for military service or severe war wounds were exempted. Anyone who was sick, over the age of sixty-five years, or in a mixed marriage was not to be included. Anyone with foreign nationality (except Poles, Soviet citizens and people from Luxembourg) was held back. Finally, anyone on the first two transports from Prague was privileged; this included many who staffed the internal administration. Outside these formal categories there were many grounds for appealing and lobbying.

Norbert Troller, a forty-six-year-old architect from Brno and veteran of the Great War, was deported to Theresienstadt in March 1942 after a spell of forced labor in a factory. On arrival he was allocated a bunk in the Sudeten barracks and commenced three weeks of manual work, as was customary for newcomers.

Troller’s Commitment

Then he was assigned to the technical department, where he designed living quarters for the inmates and also the SS. Troller quickly learned that Theresienstadt was nothing like the end of the line and that survival depended on obtaining ‘protection’ from someone in the administration who could keep your name off the transportation lists. ‘The concept of “protection”’, he wrote in a memoir, ‘was of such paramount importance for all of us that it overshadowed any other considerations.’ Nevertheless, during the interval between the transports that departed each week Theresienstadt pulsated with life. ‘There was work and leisure, concerns with sanitation, housing, health care, child care, record keeping, construction, theater, concerts, lectures, all functioning as well as possible under the circumstances.’ But as soon as word came that another 1,000 to 2,000 people had to go within a few days the population could think of nothing except ‘protection’.

Troller coolly analysed the demoralizing effect of the struggle not to be transported. ‘In fear of death one forgets, slowly at first, but then with considerable speed, the rules of ethics, of decency, of helpfulness . . . At any and all costs we try to prevent the execution of the death sentence on us and our loved ones . . . To escape that fate one had to do everything to be included in the privileged group of the “protected”.’ It was his good fortune to have skills that qualified him for the staff of the Jewish administration. His boss in the architectural office shielded him from over twenty-five comb-outs. Troller was then able to do favors for even more influential ghetto figures and, ultimately, to get work from the SS. But he was still unable to protect his sister and her daughter, who were transported some six months after they had all arrived.

Psychological Corruption

Troller bewailed the system of drawing up lists and the ‘psychological corruption’ that affected individuals as they fought one another to avoid deportation. ‘With devilish baseness and cunning they [the SS] . . . put the burden of selection on the Jews themselves; to select their own co religionists, relatives, their friends. In the end this unbearable, desperate, cynical burden destroyed the community leaders who were forced to make the selections. The power of life and death forced on the Council of Elders was the main reason, the unavoidable force, behind the ever-increasing corruption in the ghetto . . .’ But he knew he was not innocent. ‘How can I forgive myself for having succumbed to egotistical, ruthless, incomprehensible actions towards my fellow sufferers whenever danger threatened . . .’

In their determination to maintain a semblance of normal life, especially for the children, and preserve their humanity, the Jews of Theresienstadt supported an array of educational and cultural initiatives. Helga Weiss started attending classes and moved into a children’s home where she studied Czech, geography, history and maths. The youths with whom she lived shared a plethora of books and went to shows performed in attics, the only free space available for such entertainments. ‘Yesterday I went to see The Kiss. It’s playing in Magdeburg, up in the loft. Even though it’s sung only to the accompaniment of a piano, with no curtains or costumes, the impression it makes couldn’t be greater even in the National Theatre.’

Morality and Social Barriers Decay

Adults enjoyed these distractions and found more earthy satisfactions. Troller wryly observed men sneaking into the coal cellar of the women’s barracks for prearranged liaisons with their wives, who emerged subsequently with ‘coal- blackened backsides’. Marital infidelity became commonplace as traditional moral standards wilted under the threat of random extinction. Despite hunger and unmitigated body odours men and women formed relationships, some for love and others for more functional purposes. ‘

On the one hand, there was spontaneous, true, eternal love; on the other, we were faced with the continual threat of separation, sex, lust, a pressure cooker atmosphere, quick, quick, without fancy phrases, before the next transport to the east stops us . . .’ For unmarried men like Troller, especially those who were privileged, there was no shortage of girlfriends. He and a friend constructed a kumbal, a cubby-hole, in which they could have privacy and entertain. There was a strict etiquette, though. A privileged worker who possessed a kumbal was expected to offer a gift to a visiting lady friend, such as food or cigarettes. But sometimes it was just a case of satisfying an urge. One afternoon Norbert’s companion Lilly turned up at his place and announced, ‘Nori – I need a fuck, come on.’

The Diary of Philipp Manes

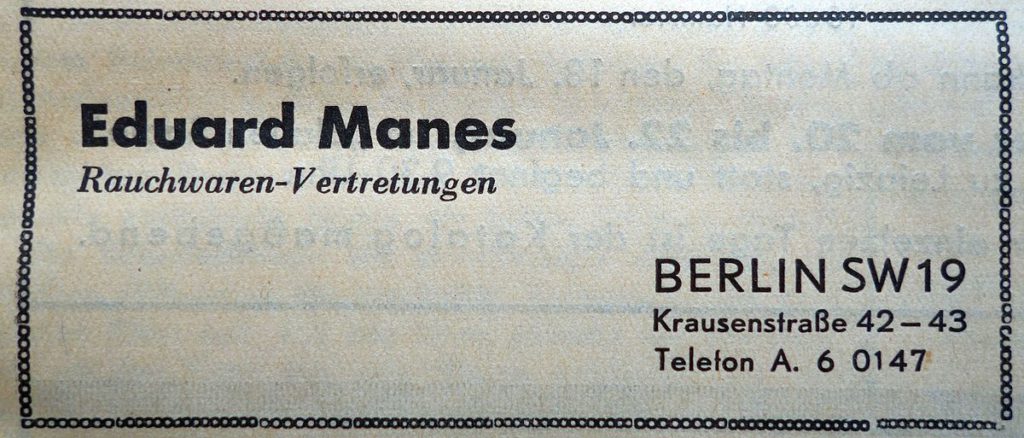

The advent of thousands of elderly German Jews dampened the defiantly exuberant atmosphere in the ghetto cultivated by the younger Czechs, but enriched its cultural life. Among the newcomers in July 1942 were Philipp Manes and his wife. Manes was a sixty-seven-year-old veteran of the Great War and holder of the Iron Cross. He had run a fur agency in Berlin until he was put out of business by the Nazis and had spent the last few months working as a drill press operator in a factory.

In his diary he detailed the last hours in the home where he had lived with his wife and where they had raised four children. ‘It seemed inconceivable that we had to give up our entire estate, leave behind everything that we had acquired over the 37 years of our marriage . . . All our possessions were to be appropriated by strangers. They would go through all the drawers and cupboards and throw out things that were worthless to them – our cherished possessions. Inconceivable.’

But at 9.30 a.m. on the appointed morning, two Gestapo officers and two Jewish marshals came to escort them to a removal van that served as transport. Hours later they were disgorged at the Jewish Old People’s Home on Grosse Hamburgerstrasse along with dozens of other deportees. The next day they were told their property had been expropriated because they were guilty of ‘communist activity’. Manes, a staunch conservative, ‘accepted this humiliation in silence’. Their passports were stamped ‘evacuated from Berlin on 23 July’ and ‘with that our life as citizens of Germany ended’.

The Shattering Truth of Theresienstadt

At three o’clock the next morning they were transported to the Anhalter Station. ‘We were cast out of the lives that we had made for ourselves, working for fifty years to see our business crowned with success . . . and now here we are with the few effects that we can carry with us in bags and backpacks.’

Along with their fellow, unwilling travelers they felt hopeful that Theresienstadt might live up to promise. What they actually found was shattering. First they were stripped of their valuables and their suitcases. For the rest of the summer Manes was condemned to wear the heavy winter clothes he had donned for the journey. They were led to a brick-walled stable and instructed to sleep on the ground. There was only a single water fountain and a disgusting communal latrine. Eventually they got their bedrolls and some personal items which they took with them to new quarters equipped with bunk beds. But this entailed the separation of men from women, and the planking for the bunks was riddled with bed bugs. Far from being a retirement home, Theresienstadt was a daily battle for life.

‘“Ghetto” signifies a renunciation of or a moratorium on morals’, Manes confided to his journal. ‘When hunger triumphed over civilized behavior and tore down all inhibitions, everyone gave themselves to one feeling and one goal: satiation at any price. Justice, security, property, and order simply yielded to this natural instinct. Those who have not witnessed how, at the end of the distribution of food, old people plunged into empty vats, scraping them with their spoons, even scraping the tables where the food was served with knives, looking for leftovers, cannot understand how quickly human dignity can be lost.’

Admiration for Czech Patriotism and Jewish Pride

After a few weeks Manes was asked by the administration to form an auxiliary to the Order Watch to assist disorientated or demented elderly Jews whose wanderings and distress caused discomfort to the rest of the populace. He used this position to start giving lectures, and before long was addressing audiences of a hundred. Eventually his talks evolved into a cultural program employing sixty-five men and women. The lectures, play readings and poetry recitals in German brought much comfort to the Berliners and Viennese Jews who were otherwise utterly adrift in the Czech-speaking environment.

Manes admired the Czech Jews for their patriotism and their Jewish pride, but he noted that they did not reciprocate this warmth. The two groups vied for power, contesting the distribution of privileges, work and rations. ‘On the one side there was abundance and the good life, which was not shared; on the other, endless hunger.’ Manes particularly resented the fact that Czech Jews were entitled to receive food parcels and seemed to get better rations from the kitchens. ‘It has to be said’, he admitted with a measure of self-reproach, ‘the Jewish Czech does not love us. He sees us only as Germans.’

Overcrowding Worsens

Even after the non-Jewish population was evicted from the town, the arrival of the German and Austrian Jews caused acute overcrowding. Combined with undernourishment due to the straitened food supply and bad sanitation, this sent the rate of mortality shooting upwards. In December 1941 just 48 Jews had died in the ghetto. Th e following March the number climbed to 259, but this was more or less in line with the increased population. In July 1942, there were on average 32 deaths per day, a total of 2,327 for August, and no fewer than 131 every day throughout September. According to Manes this was ‘the time of the great dying of the old and the very old who, with their broken, weak bodies, their worn, uprooted souls; and their unrealizable longing for their far-off children, could not resist even a mild illness.’

In September 1942 the Germans ordered the deportation of elderly Jews, to bring down the average age of the population and re-balance the number who were working. Helga Weiss was horrified at the sight of these transports. ‘Altertransports. 10,000 sick, lame, dying, everyone over 65 . . . Why send defenseless people away? . . . can’t they let them die here in peace? After all, that’s what awaits them. The ghetto guards are shouting and running about beneath our windows; they’re closing off the street. Another group is on its way . . . Suitcases, stretchers, corpses. That’s how it goes, all week long. Corpses on the two-wheeled carts and the living on the hearses . . .’

The ‘Schleuse’ (sluice) at Bohusovice Station

In two months, 17,780 aged prisoners exited the ghetto via the ‘Schleuse’ (sluice), the exit ramp that led down to Bohusovice Station. By the end of the year the proportion of ghetto residents aged over sixty-five years had fallen from 45 to 33 per cent.

Seidl insisted that the council should be restructured to reflect the ratio of German, Austrian and Czech Jews. In October, Heinrich Stahl, one of the leaders of the Reichsvereinigung, was appointed deputy to Edelstein. At the start of 1943, by which time the population was equally divided between Czechs and Germans, Seidl ordered the formation of a triumvirate consisting of Edelstein, Paul Eppstein, a member of the Berlin Jewish leadership, and Josef Loewenherz, from Vienna. Not long afterwards Loewenherz dropped out of the picture and Seidl placed power in the hands of Eppstein, with the Viennese Benjamin Murmelstein as a deputy alongside Edelstein. For the next year and a half these men would determine who would live in Theresienstadt or depart on the transports.

DAVID CESARANI, OBE was Research Professor in History at Royal Holloway, Univ. of London and the award-winning author of Becoming Eichmann and Major Farran’s Hat. He was awarded the OBE for services to Holocaust Education and advising the British government on the establishment of Holocaust Memorial Day. He died in October 2015. He is the author of FINAL SOLUTION: The Fate of the Jews 1933-1949.