by Rebecca Frankel

The canon of literature on dogs is vast and deep. I’d be willing to bet that there are thousands upon thousands of titles devoted to stories about dogs—history, fiction, memoirs, advice and “how to” books, and volumes for children. But surprisingly there were few serious studies devoted to dogs in combat, relatively speaking.

I spent nearly two years doing research, and much of that time was spent with my nose in a book – some of them nearly one hundred years old with pages scented with that musty attic smell—or searching through online periodicals of old newspapers that had been scanned and digitized. And while it might seem like it would have made the process of writing about these dogs more difficult, it actually added to the fun — a great treasure hunt to track down the more obscure books and the little-known stories they contained. And what gems there are to be found.

For instance a dog by the name of Doc, who was featured in the Des Moines Register for serving as mascot to the 23rd Iowa Infantry during the Civil War. He was known as a “patriotic pooch” who readily stood by his men through all of their battles: “At Fort Gibson he received a wound in the breast and at Black River Bridge received another in the foot.”

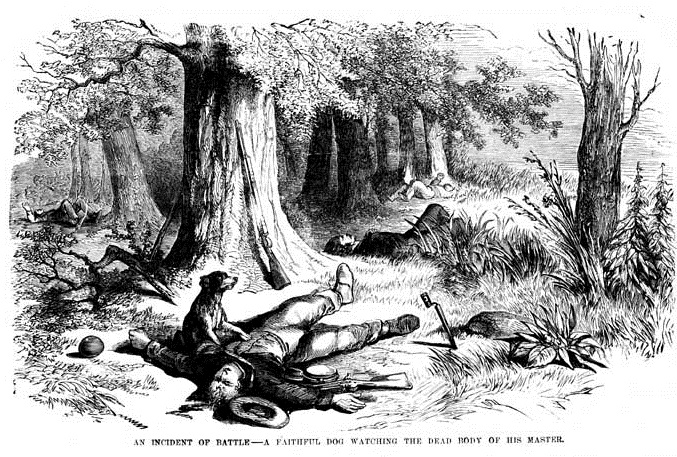

From Frank Leslie’s Newspaper, “An Incident of Battle — A Faithful Dog Watching the Dead Body of His Master.” Image is in the public domain via Civil War Monitor.

There was Union Jack, a dog who willingly — or so the reporter for Harper’s Weekly claimed — had abandoned his Confederate owner to join up with the Union soldiers. He was known to help lead them to and dig up spring water and hunt down the occasional chicken. During World War I, though the United States didn’t employ dogs in any official capacity, dogs still made the headlines of American newspapers. The New York Times ran a piece entitled “Dogs and Horses Often War Heroes” in October 1917. The interviewee, the secretary of the Blue Cross Society, spoke at length of the dogs working in the trenches saving lives as Messenger dogs and Red Cross dogs. “They know their men and possess and instinctive love for them,” she said. The Associated Press published a dispatch from Guam about a Doberman, Lucky. His handler, a Marine, was wounded and then died on the battlefield, he would not leave the body, nor would he allow anyone else to approach the body. Even the great journalist Ernie Pyle experienced the effect these dogs had on their fellow soldiers while reporting from the front lines. After one air raid a dog called Sergeant was wounded beyond saving by shrapnel and had to be put down. As he wrote in one of his reports from the front during World War II, the men grieved the dog as they would’ve any other fallen soldier, noting it was no insult to the memories of the other men that Sergeant was mourned with such feeling.

But what all of this reveals– even more so than the knowledge that there are considerably few books that explored (on their own) the history and stories of dogs in war — was that dogs really did play a consistently significant role in our wars. There might not have been a lot of them, and those that were there in the earliest instances (especially fighting in and for the United States) may not have had training or were contributing in an “official” capacity, but whatever they did offer it meant enough to the men and women around them to warrant notice and documentation – their stories were important.

REBECCA FRANKEL is senior editor, Special Projects at Foreign Policy Magazine. Her regular Friday column “Rebecca’s War Dog of the Week” has been featured on The Best Defense since January 2010. Her photo essay “War Dog,” is one of the most-viewed pieces in ForeignPolicy.com’s history and has received upwards of 16 million views and over 100,000 likes on Facebook. In 2011, she was named one of 12 women in foreign policy to follow on Twitter by the Daily Muse. Her latest book is War Dogs: Tales of Canine Heroism, History, and Love.