By Celia Stahr

Today, Frida Kahlo is one of the most celebrated artists in the world. Millions of people line up to pay homage to her work. Frida bags, bracelets, earrings, and shirts can be purchased around the globe. However, this was not always the case. In the following article, Celia Stahr, author of Frida in America, discusses how gender inequality has impacted female artists throughout history.

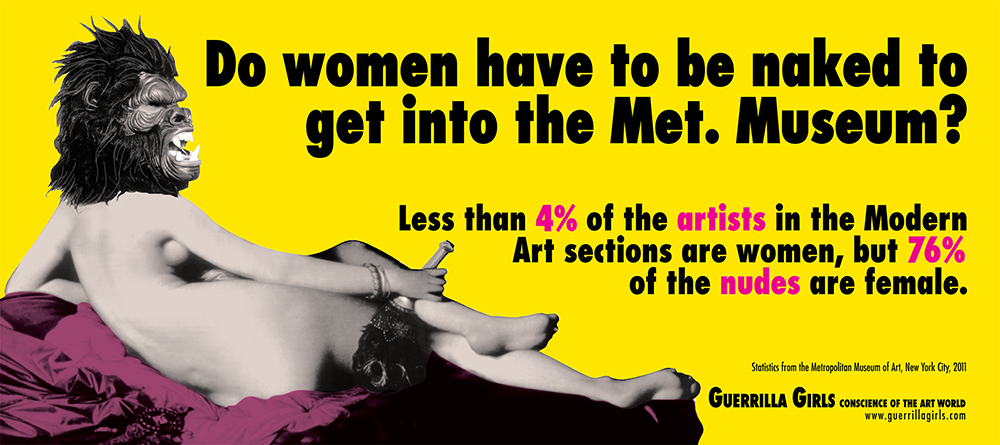

Guerrilla Girls, Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get Into the Met. Museum? Update, 2012

Copyright © Guerrilla Girls, courtesy guerrillagirls.com

On a spring evening in 1953, hundreds of excited people waited in the streets of Mexico City’s fashionable Pink Zone to catch a glimpse of Frida Kahlo and her paintings at the Galería Arte Contemporáneo. The show, Kahlo’s first in Mexico, received positive reviews, and calls from the United States and Europe came into the gallery asking about Frida’s work. It’s not surprising that this show was so popular. Today, we’re used to the adulation—“She is fearless and I love her”—and the merchandise—Frida bags, shirts, earrings, and bracelets. Frida exhibitions abound and it’s understandable why, given her propensity to draw an unusually large crowd, typically breaking museum attendance records.

What is surprising is that an artist with this type of star power once languished in the trenches of buried women artists. Although Frida had some success in her lifetime (1907-1954), it wasn’t until the 1970s and 1980s that her work started to be recognized more broadly, due, in large part, to feminist art history. With the advent of the Women’s Liberation Movement in the 1960s, feminist theory and scholarship began to enter the field of art history. Linda Nochlin led the way with her groundbreaking 1971 ARTnews essay: “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” The question in the title is one that a male gallery owner had asked Nochlin, but she realized after pondering it that it was a pointless question. Women by and large hadn’t been included in the social and artistic worlds that conferred greatness, such as art schools and art institutions, simply because they were female. Therefore, it was necessary to investigate and critique gender bias in the Western art world and to examine the societal norms in Europe, and elsewhere, that had made it very difficult for middle- and upper-class women to conceive of a professional life outside of the domestic sphere.

Since 1971, an extensive body of feminist scholarship has radically changed the field of art history and women artists have pushed the boundaries of what’s deemed acceptable for a “lady.” Women in the art world have taken to the streets to protest the lack of gallery and museum representation for women and artists of color, spawning the Guerilla Girls. These female artists, dressed in gorilla outfits, plaster the streets outside major museums and galleries with statistics exposing the unequal representation. Their ongoing tactics have helped raise awareness and, with more women entering positions of power, progress has been made. However, as we celebrate Women’s History Month in March and 100 years of women’s suffrage in the United States, it’s sobering to reflect on the fact that while nearly half of the visual artists in the U.S. are women; on average, they earn 74 cents for every dollar a male artist makes. Why? The data shows it’s because they are women.

Feminist scholars have pointed out for years that the binary oppositions prevalent within Western cultures—woman/man, intuitive/analytic, nature/culture—have served to emphasize male superiority. Thus, the word “woman” in front of the word “artist” automatically devalues the word artist. A case in point relates to the 17th-century Dutch artist Judith Leyster. In her day, she was 1 of 30 master painters who belonged to the prestigious Guild of St. Luke. After her death, her name was erased from history. Her signature was obscured on her paintings in order to sell them as works done by Frans Hals, a male artist with a similar style. An 1892 lawsuit between two London art dealers revealed that the painting Carousing Couple, thought to be by Hals, possessed Leyster’s signature. Suddenly, the painting’s value dropped by 25%. The painting didn’t change, only the gender of its maker. The assessment of artistic value, as Nochlin pointed out, is not neutral.

Unfortunately, the perception that women artists aren’t as talented, innovative, or important still prevails in the art market. Most buyers are male and auction records and studies show that they want to invest in male artists. If we use Frida Kahlo as a case study, her work provides an example of the economic disparity between male and female artists and between white Euro-American and Latin American artists. This might sound odd given Kahlo’s star status, yet her paintings have not fetched the exorbitant auction prices set by white male artists’ paintings. In 2016, Kahlo’s painting Two Nudes in a Forest, 1939, sold for eight million dollars, setting a record at that time for Latin American artists.

This price sounds impressive until you compare it to Jackson Pollock’s Number 5, which sold for $140 million in 2006 or Pablo Picasso’s Women of Algiers (Version ‘O’), which sold for $179.4 million in 2015. Two years later, Leonardo da Vinci topped Picasso’s record when Christie’s sold Salvator Mundi for $450.3 million, currently the highest amount ever paid for a painting at auction. It’s clear that the amount of money paid for an artist’s work is not based upon intrinsic value, but rather is driven by various factors, one being the gender and race of the artist.

If white male artists are seen as safe investments, as art historian Amelia Jones has pointed out, then perhaps one additional inhibiting factor for buyers of Frida Kahlo’s work would be her taboo subject matter. Traditionally in Western art, white women were primarily depicted as beautiful and alluring. In Kahlo’s self-portraits, she defies such narrow ideas, emphasizing her brown skin, her dark facial hair in the form of a mustache or unibrow, appearing in both female and male attire, and staring boldly at the viewer as if to show her power as a subject rather than as a passive object. Likewise, Kahlo’s work has typically been discussed as autobiographical, but if a woman’s status is perceived as less valuable than a man’s and a Mexican’s artist’s work less valuable than a Euro-American artist’s work, then art that specifically depicts a Mexican woman’s life will automatically be devalued in the art market.

The topic of gender and racial bias within the art world is a complex one with many different perspectives as to how to best remedy the inequalities that still prevail. In my book Frida in America: The Creative Awakening of a Great Artist, I wanted to look more closely at the obstacles and sexist and racist attitudes Frida had to contend with as she was developing her artistic voice, both within Mexico and the United States. I wanted to understand how she struggled and pushed back against the societal norms of the day, eventually coming into her own as an artist. The goal of the book isn’t to raise Kahlo’s auction prices, but rather, one of the goals is to provide an in-depth look at some of the complex cross-cultural issues she faced which were often driven by the perception that women lacked the intelligence, emotional stability, and creative genius of men, a perception that still exists today.

References

“Get the Facts,” the National Museum of Women in the Arts.

“Researchers Explore Gender Disparities in the Art World,” NPR’s Morning Edition.

“Art by Women Sells for 47.6% Less Than Works by Men, Study Finds,” Benjamin Sutton.

“Linda Nochlin on Feminism Then and Now,” Maura Reilly.

“On Sexism in the Art World,” Amelia Jones.

“The Guerilla Girls Archive,” The Getty Research Institute.

Celia Stahr is a professor at the University of San Francisco, where she specializes in modern American and contemporary art with an emphasis on feminist art and gender studies, as well as African and multicultural art. She holds a Doctorate of Philosophy from the University of Iowa and lives in the Bay Area.