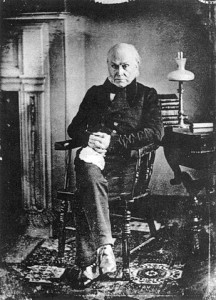

Phyllis Lee Levin

From the book: The Remarkable Education of John Quincy Adams

A patriot by birth, John Quincy Adams’s destiny was foreordained. He was not only “The Greatest Traveler of His Age,” but his country’s most gifted linguist and most experienced diplomat. John Quincy’s world encompassed the American Revolution, the War of 1812, and the early and late Napoleonic Age. As his diplomat father’s adolescent clerk and secretary, he met everyone who was anyone in Europe, including America’s own luminaries and founding fathers, Franklin and Jefferson.

In his diary entry for September 3, 1783, John Quincy Adams wrote one line: “Signature of the Definitive Treaty” signed in the Hotel d’York on the Rue Jacob. (The Continental Congress would officially ratify the Treaty of Paris on January 14, 1784.)

On September 7, he wrote of attending the theater but skipped the truly momentous news of that day in Passy, historic in terms of the fate of his family as well as his country. On that day Benjamin Franklin put into John Adams’s hands official notice of Congress’s resolution dated back to May 1, authorizing both men and John Jay, any of them “in the absence of the others, to enter into a Treaty of Commerce, between the United States of America, and Great Britain,” and in the meantime, “to enter into a commercial Convention, to continue in force, one year.”

The appointment, though official orders would not arrive until May 1784, was enough to renew John Adams’s faith in his pursuit and to refurbish his ambition. That same morning, as he explained to Abigail, the waiting had made him anxious; he was still uncertain as to how to proceed. But there was much to be done. “It is of great importance that such a treaty should be well made.” The loan in Holland required attention; when the present one was fully implemented, another must be opened, which only he or his successor could accomplish. And there were “still other things too to be done in Europe of great importance.”

Image is in the public domain via Wikimedia.com

At last, possibilities he had explored for hundreds of hours past crystallized, and his letters to Abigail were full of optimism and purpose. “Will you come to me this fall and go home with me this spring,” he asked. And would she bring Nabby and leave the boys with her brother-in-law, Mr. Shaw, the schoolmaster. As to his work, in order to save Congress expense, “I shall have no other secretary than my son. He however is a very good one.”

John Adams’s expectant note to Abigail belied his own intense problems. Suffering from a debilitating fever, he felt himself in deplorable physical condition. In general he was unhappy at the Hotel du Roi. He minded the location, at the confluence of so many streets that it was a kind of thoroughfare. Moreover, he minded the noise, the constant roar, like incessant rolls of thunder, of the stream of carriages that rolled by—only from two to five in the morning was there something like stillness and silence. Sometimes he thought it would kill him.

Read more about our other great presidents John Adams, Andrew Jackson and George Washington here

In this critical state and on the advice of his physician James Jay, “the country air being thought necessary for him, we removed from Paris to Auteuil,” John Quincy noted in his diary on Monday, September 22, to lodgings Thomas Barclay had leased from the Count de Rouault, where his father might enjoy the gardens, one full of vegetables and fruit, grapes, pears and peaches, the other, of flowers. There John Quincy Adams would take up his duties as replacement for the beloved John Thaxter, who had served his father as “nurse, physician and a comforter at Amsterdam” as well as secretary. He also managed to continue his studies, some probably begun under Dumas’s tutelage, including translation of Horace’s Odes and Caesar’s Commentaries. Auteuil was the seat of the revered poet Nicolas Boileau. Benjamin Franklin’s friend Madame Helvetius lived a few doors away. But neither medicine nor diet, the tranquil views of the village of Issy, of the Castle Royal of Meudon, of St. Cloud and of Mont Calvare, nor walks in the Bois de Boulogne, nor rides on horseback provided a cure. Not even the garden, which John Adams acknowledged was of excellent quality, despite his complaint that “every thing suffers for want of manure.” Though he had recovered from his fever, he was still “extremely emaciated and weak.”

Urged by friends to take the waters at Bath, John planned for a six-week visit. But first there was to be a stay in London, which he had contemplated for several months before his present illness. Prior to learning of his new commission, John’s anger with his government was clear in a letter to Abigail: “if I cannot obtain leave, I must take it.” But that anger was tempered by eloquent praise of John Quincy Adams. John planned to “take my son with me, whose company is the greatest pleasure of my life.”

Father and son and one servant, Leveque, left Auteuil on Monday, boarded a packet boat at Calais at 9 a.m. Thursday morning, October 23, 1783; 18 hours later, a pilot boat put them on Dover’s shore at 3 a.m. They had suffered a horrendous voyage, “never before so sea sick, nor was my son,” the father wrote. One day and 72 miles later, having asked to stay at the best inn in London, they were carried off to Osborne’s Hotel in the Adelphi Buildings. To their surprise they found themselves in a street marked “John’s street”; the postilion turned a corner, and they were in “Adams- Street” and “I thought surely we are arrived in fairy land. How can all this be?” John Adams had wondered.

Image is in the public domain via Wikimedia.com

Quincy’s future wife, Louisa Catherine Johnson, was present, she was then eight years old.

…

By October 1 John Quincy Adams felt settled but found his studies far more arduous than he had counted on. Greek was to be “the grand object” that claimed his greatest attention. He was to master nearly all of the New Testament and between three and four of the eight volumes of Xenophon’s Cyropaedia, plus five or six books of Homer’s Iliad. More secure in Latin, he had already done part of Horace’s four books of lyric poetry. In English, he had to study Watts’s Logic: Or, The Right Use of Reason in the Enquiry After Truth and John Locke’s Human Understanding, and something in astronomy.

Given the formidable task ahead, he felt obliged to ask Nabby for a temporary suspension of their agreement to write frequently, at least until he got to Cambridge. He planned to do little socializing in Haverhill, and he anticipated a continual sameness in the days ahead, which meant that he should have little of interest to write her. Still, he would set apart half an hour two days a week to write at least something.

Studying through the winter, progress was painfully slow at times. Getting through 100 verses in the Old Testament was relatively easy, though it was time-consuming to look up the vocabulary. But the more he read in both Greek and Latin, the more deeply he admired both the classic and the lyrical poets. He felt rewarded for all his pains in making the acquaintance of Virgil and in Horace he found many “noble sentiments.” The Latin lines copied into his diary may have had deep personal resonance for him; in translation, they read, “Cease to ask what the morrow will bring forth, and set down as gain each day that fortune grants!”

Initially, on arriving at the Shaw home, John Quincy Adams had been glad his trunks were delayed: the lack of decent clothes provided him with an excuse to refuse invitations. He was not eager to make new acquaintances given his experience of the last eight years: no sooner had he made friends, he had been obliged to leave them, probably never to see them again. As a result, his heart, “instead of growing callous by a frequent repetition of the same pain, seem’d to feel every separation more than any of the former ones.” Not for the first time he declared himself “really weary of this wandering, strolling kind of life” and vowed to “form few new acquaintances, have few friends,” but such as he might—quoting Hamlet—“Grapple to my heart with hooks of steel.”

In spite of his intense resolve, he did make new friends with members of a prosperous Haverhill family, the Whites; he enjoyed his first Thanksgiving celebration, a recently established custom determined by the governor of Massachusetts on December 15, and seemed a bit disappointed that Christmas, “a great and important day among Roman Catholics and the followers of the Church of England,” was not observed in this country, nor anywhere, he believed, by the dissenters.

Nevertheless his preparation for Harvard was his first priority. Unforeseen interruptions were inevitable, but where he could help it, he remained focused. His Aunts Mary and Elizabeth were keenly aware of their nephew’s motivation and commitment. Both women were sympathetic, but only to a point. They frankly disapproved of his sleeping habits. Elizabeth wrote that her nephew was not quite so fleshy—she had written “fat” in the initial draft—and wasn’t prey to distractions; to the contrary, “he was too much engaged to suffer any thing but sickness or death to impede his course.” Mary, in the same sentence that she assured Abigail that Cousin John, as she called her nephew, had not lost his studious disposition by coming to America, also told her sister that she was almost afraid to let her children visit Haverhill this last vacation lest they interrupt him. And because he never retired before one o’clock in the morning, she feared “he would wear out both body and mind.”

Had Aunt Mary been privy to her nephew’s diary, she would have learned that he could not study in the morning because the household was so busy, “but that when every body else in the house was in bed, I have nothing to interrupt me”—hence the late hours.

Predictably, given the realities of his life in Haverhill, John Quincy Adams admitted to an “impatient state of mind.” Early on he had fretted about how to continue with his journal, facing as he did a continual repetition of one day like another. But then he decided that his approach would be different: “Little narrative, and the most part of what I write will be observations.” It was to be the same with his letters, in which with disarming, if not reckless, candor, he would dramatize not only his “family values,” but his moral, emotional and philosophical struggles to bridge the transition from a worldly life abroad to the confines of “so small and retired a town as this.”

…

On Monday, June 30, John Quincy Adams left Boston for Philadelphia to report to President George Washington for instructions, traveling first to Providence, then down the river to Newport. He then sailed toward New York on the Romeo and, owing to a dead calm, had to row from Hell Gate into New York City, where he stayed for three days with his sister Nabby and her husband, Colonel Smith, in their home at 18 Cortland Street. Dinner guests that day included Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Perigord and Bon Albert Briois de Beaumetz; also Louis Saint Ange Morel, Chevalier de La Colombe. John Quincy Adams wasn’t surprised finding these famed Frenchmen at the Smiths’ table. His father had commented on the great number of men of talent in the United States—not only from France but from Switzerland, England, Scotland and Ireland—and feared they would do more harm than good “if ‘we are not upon our guard.”

Image is in the public domain via Wikimedia.com

Still, they were an impressive group with memorable pasts: Talleyrand, bishop of Autun and ambassador to England; Beaumetz, a prominent member of the National Assembly of France; Colombe, aide-de-camp to the Marquis de Lafayette during the American Revolution, who had escaped from Austria where Lafayette remained imprisoned. Both had been promoters and victims of the French Revolution. John Quincy Adams found Talleyrand reserved and distant, Beaumetz more sociable and communicative. He and Colombe had spoken for half an hour before they realized they had been fellow passengers on the Sensible nearly 16 years ago. Now banished from France and from England, it seemed that America, “this country of universal liberty, this asylum from the most opposite descriptions of oppression,” was the only one in which they could find rest. Obviously quite taken by his formidable companions, it was natural to look with reverence, or at least with curiosity, so John Quincy told himself, on men who have been so highly and so recently conspicuous upon the most splendid theater of human affairs.

But parties had successfully destroyed one another, and in the general wreck it was not easy to distinguish between those whose fall has been the effect of their own incapacity, and those who have been only unfortunate. As he wrote his mother, “tempora mutantur et nos mutamur in illis,” “The times change and we change with them.” Presently, Talleyrand and Beaumetz were exploring business opportunities on behalf of themselves and friends abroad, particularly investments in land. That probably accounted for their presence at the Smiths, the colonel momentarily being a vastly successful landowner in 1794.

But truly, he thought the times unique, that “Perhaps there never has been a period in the history of mankind, when fortune has sported so wantonly with reputation, as of late in France.” The tide of popularity ebbed and flowed with nearly the same frequency as that of the ocean, though not with the same regularity. The list of the fallen was long, including Necker, Lafayette, Petion, Condorcet, Brissot, Danton and “innumerable others [who] have in their turns, been at one moment the idols and at the next the victims of the popular clamor. In the distribution of fame, as in everything else,” he wrote in his diary, “they have been always in extremes.”

Phyllis Lee Levin is the author of several books including The Remarkable Education of John Quincy Adams. She has been a reporter, editor, and columnist for The New York Times and lives in Manhattan.