by David Downie

Romantic-era novelist Alexandre Dumas may well have created the world’s first fiction factory in Paris in the mid-1800s, a factory populated by ghosts. How many of Dumas’ hundreds of millions of readers realize that the plots and treatments for some of his mega-bestselling novels were written by others, one man in particular, a man sometimes known as the “fourth musketeer?”

I had heard vaguely about such allegations before I set out to spend time with Dumas while researching my latest book on Paris, Romanticism and romance. Then a curious thing happened.

While visiting the “Romantic corner” at my favorite graveyard anywhere—Père-Lachaise Cemetery—I stood wondering whether instead of being in the Panthéon across town Alexandre Dumas would not have been happier here. After all here were his friends novelists Honoré de Balzac and Gérard de Nerval, painter Eugène Delacroix and scores of other Great Romantics.

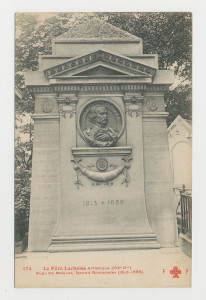

Maquet’s tomb at Père Lachaise in Paris. This image is in the public domain via Paris Cemetaries.

When I wandered downhill from Balzac’s handsome tomb (it’s topped with a bronze sculpture of the perennial, prolific writer) perhaps 50 yards south in Division 52 I stopped to admire another fine tomb I’d never noticed before.

It turned out to be the resting place of fellow Romantic and prolific writer Auguste Maquet. Who was he? Adorned with a low-relief effigy of Maquet the tomb was also carved with the titles of books Maquet had written—or had supposedly written. I read the titles and read them again.

Mustachioed and topped with a head of flowing locks, had Maquet really written or perhaps co-written The Count of Montecristo and The Three Musketeers? Surely those were the masterpieces of Alexandre Dumas?

Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870). This image is in the public domain via Wikipaedia.

What I soon learned is Maquet and Dumas actually began writing novels together, but Maquet’s name never appeared on these books. Their de facto partnership evolved into a complex ghosting relationship, with Maquet writing plots, treatments and first drafts, and Dumas filling out, polishing and improving their books—though sometimes he only changed a few lines or words. The pair collaborated on nearly 20 books and a number of successful plays.

The more successful the Dumas-Maquet team became, the more ghosts were needed. Maquet was not the only writer flanking Dumas. There were many other ghosts. The difference between the lesser phantoms and Maquet was fundamental: Maquet and Dumas had begun on an equal footing. It was their publisher’s decision to use Dumas’ and not Maquet’s name that determined their fates.

At the time many in the publishing business knew Maquet did much of the writing for Dumas. That is why, after many years of working together, Maquet demanded to be paid a share of royalties and also wanted credit: he demanded his name be put on the cover of their books. Dumas refused. Maquet sued Dumas three times and finally won a lawsuit. The settlement ensured Maquet would be comfortably off: he received royalties and back payments. But his name was kept off the book covers. Why?

The answer is simple: branding. Publishing was a sophisticated business in Paris even in the early and mid-1800s. Once an author’s brand had been established it was in everyone’s commercial interest to continue with it.

Maquet was no slouch. A thoroughgoing Romantic with a capital “R” he was a poet, playwright and well-known party boy in his day. He published 13 novels and 7 plays in his own name. Handsome, rakish and always well-turned-out in the style of a Paris dandy, Maquet was a regular at the literary salon where Théophile Gautier and Gérard de Nerval hung out among other wild, spirited Romantics. Maquet knew the greatest Romantic of them all, Victor Hugo.

Curiously, Auguste Maquet’s many novels written under his own name—all of them very much like those he wrote with or for Alexandre Dumas—were not as successful as those of his flamboyant partner.

Is that why Maquet disappeared from the radar screens? It’s difficult to say. Perhaps Dumas’ wit, humor and insouciant flair were the essential ingredient in their co-written works. Dumas had a way with people and publicity. He was charismatic and unstoppable.

Even when everyone knew the secret truth about his relationship with Dumas, Maquet never enjoyed the popularity or fame of his rival but he became well-off and lived comfortably. He died unknown and is only now being rediscovered: a street in Paris is named for him, and a movie about him came out in 2010.

Dumas, instead, was famous, beloved and revered but wound up ruined and bankrupt. Dumas died a pauper. Maquet thrived but disappeared. Dumas like Victor Hugo and the nation’s great and good is buried in the Panthéon. No other French writer has sold as many books as Dumas—and they continue to sell. He has a cult following but who remembers the roller-coaster of his life?

David Downie, a native San Franciscan, lived in New York, Providence, Rome and Milan before moving to Paris in the mid-1980s. He divides his time between France and Italy. His travel, food and arts features have appeared in print publications worldwide. Downie author of A Passion for Paris: Romanticism and Romance in the City of Light,is co-owner with his wife Alison Harris of Paris, Paris Tours custom walking tours of Paris, Burgundy, Rome & the Italian Riviera. He is the author of other critically acclaimed work such as Paris, Paris, and the bestselling Paris to the Pyrenees.