by Janice Hadlow

Queen Charlotte of Mecklenberg Strelitz, the wife of George III, has never enjoyed a particularly good press. During her lifetime, and in the nearly two hundred years that have elapsed since her death in 1818, she has been criticized for being ugly, mean, obsessed with empty protocol, a snuff-taker and German. Not all these accusations were totally without foundation. Some indeed were made by her own family, who poked gentle fun at her habit of exclaiming “So!” in the German intonation she never lost, before reaching for another pinch. Her daughters in particular knew that she was not always an easy person to live with, and as she grew older and more bitter, she became, even for those dutiful sisters, increasingly hard to love. But she had a great deal to bear. And like most characters, Queen Charlotte’s personality was in truth a mixture of light and shade, kindness and truculence, sympathy and selfishness.

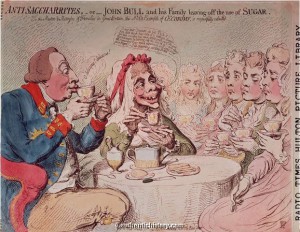

Image is in the public domain via Commons.Wikimedia.org

As with anyone’s story, much depends on the perspective one takes. There is no shortage of images showing Charlotte in the harshest possible light. All her life she was a target for the caricaturists, who gleefully portrayed her as a haggard, greedy, manipulative virago. But a little familiarity with the realities of her life reveals a very different Charlotte. She was:

- a woman of strong feelings whose circumstances made it all but impossible for her to express them;

- a woman of huge intellectual appetite that was never properly satisfied or acknowledged;

- a woman who endured decades of childbearing, but was unable to devote herself to the rearing of her sons and daughters in the way she would have wished;

- a woman horrified and humiliated by her husband’s sudden and inexplicable descent into madness; and above all,

- a woman increasingly conscious of the loneliness and limitations imposed upon her by her royal role, but incapable of escaping it

Charlotte’s nature was never one of simple, sunny cheerfulness; she was always a more complex figure than that. In later life, the pressures she endured accentuated her darker qualities and drove her inward upon herself. But as a young woman, she was a very different person, playful, lively and sprightly. She loved balls and concerts, was an accomplished harpsichord player. She enjoyed the theater and the opera, although she thought London performers vastly inferior to those in her native Germany.

As a young mother, she was passionately committed to family life, hoping to break with royal tradition and involve herself directly in the upbringing of her fifteen children. An avid reader of Rousseau’s Emile, the C18th’s best-selling book on child-rearing, Charlotte aimed to raise her brood in the modern way, giving them a freer life, spent in the open air, unconstrained by formal clothes, and as far removed as possible from the artificial world of the court. It was a huge disappointment to her that her duties made it impossible for her to immerse herself in the family project as deeply as she yearned to do.

A clever, bookish woman herself, Queen Charlotte was a quiet but determined advocate of a proper education for girls. She supervised the studies of her daughters very closely, and was often to be found haunting their schoolroom, urging them onto to ever greater efforts. Although she decreed her daughters should learn the embroidery skills that she herself excelled in, she also designed a wide curriculum for them that included modern languages, philosophy and even a “course on electricity” which she herself attended, book in hand. No-one knew better than Charlotte how important a good education could be as a resource for a royal woman. She considered her own intellectual interests had often rescued her from boredom and despair.

Image is in the public domain via laura-cenicola.de

Much of Queen Charlotte’s life was about repression and denial. She learned early on that it was easier to adopt a prudent silence than to strive against restrictions she could not change. Her strong sense of duty and obligation meant that she rarely contradicted her husband, a position which he fully encouraged her to adopt. Publicly, Charlotte always “put on a good face” but, as her letters to her brother show, in private, she was often far more conflicted. To him she revealed many of her deepest hidden feelings – her impatience with court life, the loneliness and isolation she endured, even the frustration she felt at the twenty years she had spent childbearing, confessing that she longed, “to see the end of my campaign.” Most radically, she expressed an opinion that would never have escaped her lips in public. “If women had the same opportunities as men, they would do just as well. “

To some extent Queen Charlotte colluded in her own unhappiness. She was not forceful enough to reshape the circumstances of her life, and grew increasingly resentful and miserable as a result. But she had her own kind of courage; she was bowed and sometimes overwhelmed by events, but never destroyed by them. There was always much more to Queen Charlotte than was revealed at first glance.

JANICE HADLOW is the author of A ROYAL EXPERIMENT: Love and Duty, Madness and Betrayal the Private Lives of King George III and Queen Charlotte and has worked at the BBC for over two decades. During the last ten years she ran BBC Two and BBC Four, two of the broadcaster’s major television channels. She was educated at Swanley School in Kent, and graduated with a first class degree in history from King’s College, London. She currently lives in Bath. A Royal Experiment is her first book.