by Roger Clarke

‘Just before I died, I went blind, and then I had an ’aemorrhage and I fell asleep and I died in the chair in the corner downstairs.’ (the voice of an old man expressed by a 12 year-old girl at Enfield, England, 1977)

One of the chapters I considered writing for ‘A Natural History of Ghosts’ was a one on the Enfield Poltergeist and whether it had been at all influenced by The Amityville Horror™ in the USA.

What was the Enfield case? In August 1977 a single mother called Peggy Hodgson called the Emergency Services to report loud knockings and furniture moving by itself. The police officers who attended the scene witnessed some phenomena and the Daily Mirror sent a reporter to cover the story. The Society for Psychical sent members Maurice Grosse and Guy Lyon Playfair to investigate. They found the activities, such as they were, focused on the two young girls living there with their two younger brothers who rarely figure in any of the accounts.

Grosse and Playfair moved into the Enfield House in September 1977, which also happens to be the year and month that the book about the Amityville haunting was published in the UK. They had an uphill battle in some ways: the SPR was institutionally cautious when it came to poltergeists. Were they for example living or were they dead? SPR legend Frank Podmore (1856-1910) considering them simply the product of misbehaving children.

The Amityville case had been the subject of countless films and books since 1975. Most readers of this blog will have heard of it, and so there seems little point in my going over one of the most examined proto-ostension cases in history. In a nutshell the Lutz family fled their suburban family home after they’d apparently been haunted; it was all pig-headed demons, hallucinations, murdered boys, flies and slime. As with the Enfield case a confession of fraud was admitted and then retracted.

***

1977 was an interesting year in the United Kingdom. It was the summer of the Silver Jubilee and the Sex Pistols and things would never be the same again.

According to government figures (the UK Gini coefficients) in 1977 the gap between the rich and the poor has never been more slender; I only mention this because the family at the centre of the Enfield case were working class/ blue collar and they lived in subsidised public housing/council houses. There was a tendency in the UK to associate the poltergeist with the poor, and they were sometimes called ‘council house ghosts’.

‘Council House Ghost’ was a calculated insult: it suggested a family too superstitious, unlettered and blue-collar to be trusted. There was a history in England of little girls and psychic fraud and everyone remembered how the Cock Lane Ghost had damaged the reputation of even the mighty intellectual Dr Johnson in 1762.

At that time Maurice Grosse moved into the Enfield house he had recently been bereaved and was in some ways acting out an elaborate response to grief with these two surrogate daughters – one of whom shared the same name as his dead daughter Janet. Both he and Playfair had free access to the environment that simply wouldn’t be possible now.

Grosse and Playfair were a classic head-and-heart duo. Grosse had the emotional and empathetic skills needed to help the family, counsel the mother and children and keep things as calm as possible. Playfair had the clear analytical mind. ‘This House is Haunted: The True Story of a Poltergeist’ (1980) remains pretty much the only source of information on the subject, apart from a few press stories from 1977 when journalists tried to cover it and some recent interviews from the grown-up girls.

What we have from those months of fall, 1977, are a real shopping list of classic poltergeist activity – by one estimate, 2,000 logged incidents. There were more than 30 witnesses to events. Heavy furniture would amble across the room. Huge fireplaces would be ripped from their fittings. Fires were lit spontaneously and pools of water would appear. Obviously faked incidents were also logged – reckoned to be about 2% of the total.

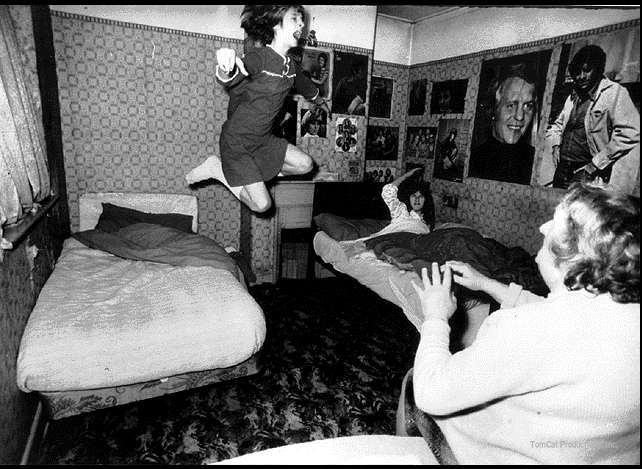

Grosse witnessed the 11 year-old Janet being dragged around by the feet — now a common trope in horror movies but then almost unheard of. Was she really seen levitating while asleep with Lego bricks and toys swirling round her in a multi-coloured plastic vortex? More creepily Janet manifests the voice of an old man who claimed to have died in the house; here’s Maurice Grosse revising the tapes.

American paranormal investigator Ed Warren concluded that the children were the subject of demonic possession — of course he would. US ghost belief is by default 17th Century Jacobean, despite the later accretions of Roman Catholicism and the elaborations of Hollywood (most perfectly realised in the film ‘The Exorcist’ — belief in possession in the US was relatively rare before this film came out).

Jacobean Metaphysics came over with the Founding Fathers. Ghosts were never spirits of the departed but ‘simulacra’ — demons pretending to be the departed. Since there was no purgatory in Protestant thought, there was nowhere for ghosts to come from. Hell was locked and why would anyone leave Heaven?

Looking back on those images of the rooms, the girls’ bedrooms with their David Soul posters have a strange quality. Everything is so dowdy and poor and buck-toothed provincial compared to the middle-class murder-glamour satanic-majesty of the Amityville case, but maybe, in some strange way, that is its humble power. And maybe, amongst all that ordinariness, something haunted and vestigial did creep through into the minds and lives of that family all those years ago.

One more observation. Between June and August a TV series ‘The Supernatural’ was broadcast in an era when there were only three TV channels in the UK and every TV show was an event. The last episode Dorabella was broadcast on 6th August, 1977.

The events at Enfield began three weeks later. I wonder whether the Hodgson family watched it?

Here’s Hollywood scriptwriter Jane Goldman having a poke around the house at Enfield and here’s a 2012 interview with the grown-up Janet (Winter). Here’s the house on Green Street where everything happened.

ROGER CLARKE is best known as a film-writer for the Independent newspaper and more recently Sight & Sound. Inspired by a childhood spent in two haunted houses, Roger Clarke has spent much of his life trying to see a ghost. He was the youngest person ever to join the Society for Psychical Research in the 1980s and was getting his ghost stories published by The Pan & Fontana series of horror books at just 15, when Roald Dahl asked his agent to take him on as a client. His latest book is Ghosts A Natural History: 500 Years of Searching for Proof

1. Folklorists might argue this was more pseudo-ostension but the story seems a medley of pre-existing stories, adaptations of pre-existing stories, and new stories specific to the Lutz family pathology.↩