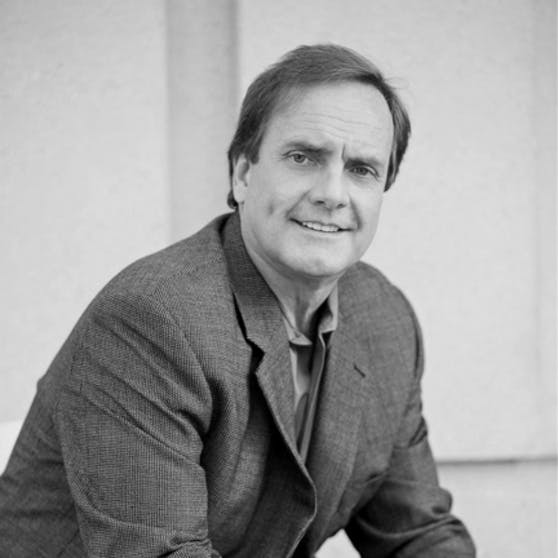

by Philip Jett

Many believe that the most melancholy couple in the White House must have been the Lincolns. They endured the horrific American Civil War and suffered the loss of a child while in office. Only one of their three sons lived to carry on the Lincoln legacy. A credible case can be made, however, that it was not the Lincolns, but the Pierces, who bore the greatest burden of grief while in the White House.

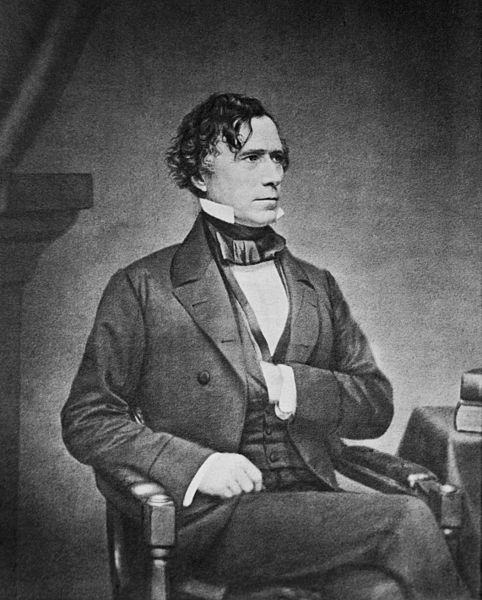

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

Franklin Pierce was inaugurated as the fourteenth president of the United States in March 1853 at the age of forty-eight, making him the youngest president up to that time. Nearly twenty years earlier, Pierce had married Jane Appleton, also of New Hampshire. Painfully thin and shy, Jane Pierce suffered from physical and psychological ailments most of her life. She hated politics and urged her husband to resign as a U.S. Senator in 1842 after the birth of their third son. Devoutly religious, she had convinced herself that God had taken their first two sons—a newborn and later a four-year-old—because of her husband’s political ambitions. Thereafter, Ms. Pierce forbade her husband from accepting political appointments and nominations, fully expecting him never to serve in public office again.

A decade later, however, after failing to nominate several candidates for president at its 1852 convention, the Democratic Party settled on a relatively unknown pro-slavery Northerner—Franklin Pierce. When Jane Pierce received the news that her husband had accepted the unanticipated nomination, she reportedly fainted. The Pierces’ only living son, Benjamin “Benny” Pierce, then eleven years old, shared his mother’s contempt for politics, as evidenced in a letter to his mother: “I hope he won’t be elected for I should not like to be at Washington and I know you would not either.” Though Pierce did little campaigning as was the custom of the time, he won the election handily. In an attempt to pacify the First Lady-to-be, Pierce explained that Benny, whom she adored, was now assured of a better future as the son of a U.S. president.

Two months later, on January 6, 1853, the Pierces were returning home after attending the funeral of Ms. Pierce’s uncle in Boston. Despite being the president-elect, Pierce rode inside a single 72-passenger Boston and Maine Railroad train car just like everyone else—the rich and the poor, the important and the insignificant. Secret service protection of presidents did not begin until 1902. He and Ms. Pierce sat on one bench and Benny sat across facing them. Just past Andover, Massachusetts, the train car’s axle snapped in two, causing the wooden car to derail, somersault down an embankment, and smash into a pile of boulders, where it splintered into fragments. Miraculously, everyone on the train survived, except for Pierce’s only remaining son—Benny.

“Master Pierce lay upon the floor of the car, with his skull crushed in the most frightful manner,” read the January 14, 1853, issue of The Liberator (Boston). “The cap that he wore had fallen off, and was filled with his blood and brains. This was the horrid sight that met the eyes of Mrs. Pierce when she regained consciousness.”

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

The natural order of death had been broken for the Pierces yet a third time. They suddenly found themselves childless. All of the promises of Benny’s life to which the Pierces had looked forward—a child’s companionship, school graduation, career, marriage, and grandchildren—had died, too. Even their memories, fused with guilt, were overshadowed by the horrific image of their dead son’s crushed skull. And this was at a time when psychiatry consisted principally of “lunatic asylums” dedicated more to confinement than treatment.

With his wife flirting with madness and his own mind muddled, Franklin Pierce departed New Hampshire for Washington, D.C. merely seven weeks later to attend his presidential inauguration. Pierce was terribly affected by his son’s gruesome death. When affirming his oath of office during his inauguration, which his wife did not attend, Pierce chose to place his hand on a law book rather than the Holy Bible. “You have summoned me in my weakness, you must sustain me by your strength,” Pierce proclaimed to the crowd.

There’d be no grand inaugural ball, no smiling First Lady wrapped in an extravagant gown, and no rambunctious Benny. For nearly two years, Jane Pierce remained in the upstairs living quarters of the White House, spending her days writing letters to her dead son and participating in séances. She became known as the “Shadow of the White House.” It wasn’t until New Year’s Day, 1855, that she at last descended the stairs, more like an apparition than a first lady, to attend a public reception held at the White House.

President Pierce, on the other hand, found comfort in 80-proof spirits. Already a fervent drinker, Pierce attempted to escape his emotional distress and nightmares by even heavier imbibing, which only contributed to his lack of concentration and his inability to make decisions. To add to his misery, the religiously zealous and slightly deranged First Lady continued to blame him and his political ambitions for Benny’s death. Still, he had no choice but to perform the duties of the highest office in the United States to the best of his ability, no matter how heartbroken, miserable, and drunk he might be.

When President Pierce failed to receive the nomination for reelection from his own party in 1856, he is reported as saying, “There is nothing left to do but get drunk.” It would be a pastime that he would continue to pursue the rest of his life, dying at the age of sixty-four from cirrhosis of the liver. Jane Pierce had died four years earlier at the age of fifty-seven of tuberculosis.

History books opine that Franklin Pierce’s presidency was one of the worst, if not the worst of all. It is true that Pierce believed slavery was protected by the U.S. Constitution. To that end, he signed the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 allowing each territory to decide slavery within its borders. Most historians believe the law lit the fuse that eventually exploded into the American Civil War. Perhaps President Pierce would have been an inept president even if his son had not been killed so horrifically before his eyes. After all, President Lincoln is thought to be the greatest U.S. president and he not only experienced the loss of two sons and the constant strain of managing a depressed, if not demented, wife, but he also had to overcome bad news from the battlefield each day. Pierce simply did not possess Lincoln’s strength of will and leadership.

Regardless of whether the Lincolns or Pierces carried the heaviest burdens of grief in the White House, one thing is certain—if ever a president and first lady had a sympathetic explanation for their poor performances in the White House, it would be Franklin and Jane Pierce.

Philip Jett is a former corporate attorney who has represented multinational corporations, CEOs, and celebrities from the music, television, and sports industries. He is the author of The Death of an Heir: Adolph Coors III and the Murder That Rocked an American Brewing Dynasty and also Taking Mr. Exxon: The Kidnapping of an Oil Giant’s President. Jett lives in Nashville, Tennessee.