by Nina Sankovitch

On a late winter’s evening in the year 1902, Amy Lowell took to the podium at a meeting of the Brookline school board to protest the reappointment of an aged and ineffective teacher. The audience was shocked by this Boston Brahmin woman speaking out in public, and even more horrified that she was taking a stand against an older, established male.

Amy didn’t care; she kept on making her arguments against the man and in the end, her position was adopted by the board and the man was not re-appointed. When Amy finally descended from the dais, however, her family members surrounded her, pulling her from the meeting hall as they chastised her for speaking out as a woman.

What a surprise then, six years later, when Amy’s older sister Katherine (Katie) Roosevelt Bowlker asserted herself in the public sphere by founding the Women’s Municipal League of Boston. For the next ten years, she would be the organization’s President and guiding light, and at times its very public voice. She would use that voice to direct criticism and propose improvements to male-led civic institutions long considered outside the realm of women.

The members of the Women’s Municipal League came mostly from Katie’s own family and social circles, women born and bred Brahmin but now wanting to give back to the larger community in which they lived. Katie wanted to lead these women in what she called “municipal housekeeping.”

She wrote in 1909 that women “are better fitted than men, by their training, to understand, and therefore to improve city conditions, in those directions which we have grouped under the general name of municipal house-cleaning, and municipal home-making, using these words with their largest meaning…”

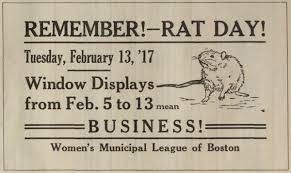

Katie didn’t mean sweeping stoops and dusting front parlors. The issues she wanted the League to focus on included the needs of immigrants, city housing, sanitation, the care of streets and alleys, waste disposal, rat and vermin eradication, and air quality (what she called “the smoke nuisance”).

Katie planned the work of the Municipal League to function along three main criteria: first, to educate women on the workings of local and state government regarding each issue identified by the League as important, and thereby empower them to influence the workings of government; second, to launch women-led volunteer programs aimed at improving quality of life for all classes of Boston women; and third, to institute experimental programs aimed at improving health and welfare that would be so successful the city itself would be inspired to take over the experiments and implement them city-wide.

Katie planned the work of the Municipal League to function along three main criteria: first, to educate women on the workings of local and state government regarding each issue identified by the League as important, and thereby empower them to influence the workings of government; second, to launch women-led volunteer programs aimed at improving quality of life for all classes of Boston women; and third, to institute experimental programs aimed at improving health and welfare that would be so successful the city itself would be inspired to take over the experiments and implement them city-wide.

A project pursued by Katie’s sister Elizabeth (Bessie) Lowell Putnam met all these criteria. Long interested in issues of infant and child health, under the auspices of the Municipal League Bessie now turned to the question of prenatal health.

Her own mother had suffered through pre-eclampsia-related problems in pregnancy that left her an invalid for most of her life. Bessie sought to find out the latest information on ensuring maternal health, and then approached the League with a proposal.

With the support of the other women, Bessie set up the first ever prenatal clinic in the United States. It was a small clinic, sited just next door to the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital on Francis Street. Women who registered their pregnancy with the hospital were sent to the clinic and put on a rotation of weekly visits from a nurse, along with in-clinic care when necessary.

There was outreach to bring other expectant mothers in, including those who might not even think to go to a hospital before giving birth. All these women were followed up with care throughout their months of pregnancy and up until birthing day.

During the first year of the clinic, not one woman treated died in childbirth, although three had suffered from pre-eclampsia (and were successfully treated for it). Out of the two hundred and five babies cared for in the first year of the baby clinic, only four died. This was a huge improvement over previous years in Boston, both for rate of childbirth deaths and of infants dying.

The Municipal League opened two more prenatal and baby clinics, and within a few years, Brigham Hospital and Boston Lying-In Hospital took over the clinics – just as Katie had planned for, in her initial guidelines for Municipal League projects.

Empowering women in their health, in their home, in their community: that was Katie’s goal. When first forming the League, she argued that “women of every occupation, of every interest, of every degree of poverty and wealth…[can] gain the stimulus and up-lift that comes from feeling themselves members of the great municipal body of women, who are all striving together for one common end – the making of the city in which they live, a cleaner, healthier, and a happier place for its citizens.”

Katie predicted, correctly, that the time had come “when all women can unite together to form an intelligent, concerted body of public opinion, which shall be so representative, and so influential, that no public official can disregard its desires.”

When asked about women’s right to vote, Katie offered a diplomatic response, officially stating as President of the Municipal League that “if the suffrage shall eventually come… the League will have proved its usefulness in serving as the best possible means of educating people to vote intelligently. If the suffrage shall never come, we believe that the League will equally have proved its value in showing how great is the work that women can do, without the vote.”

NINA SANKOVITCH is the author of The Lowells of Massachusetts: An American Family and Tolstoy and the Purple Chair and Signed, Sealed, Delivered: Celebrating the Joys of Letter Writing. She was born in Evanston, Illinois and is a graduate of Evanston Township High School, Tufts University, and Harvard Law School. She lives with her four children, husband, and three cats in Connecticut.