by Tom Clavin

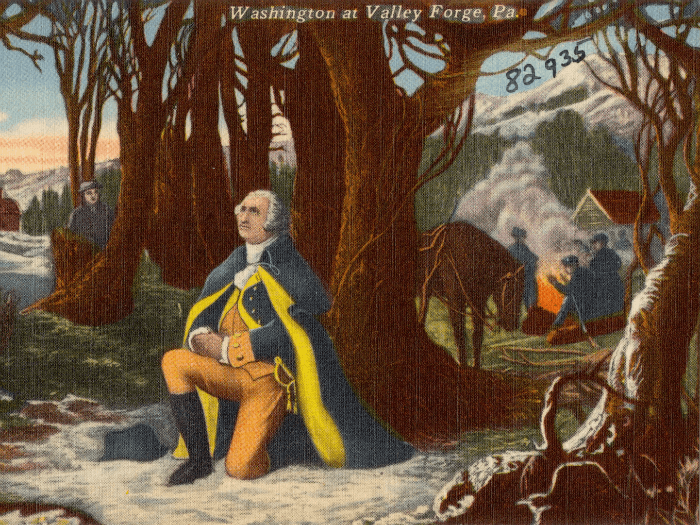

Some people think there was a Battle of Valley Forge. There could well have been, because 2,000 American soldiers died there. Or what we know about Valley Forge is an illustration we saw in middle-school Social Studies textbooks, one that showed a few guys freezing in the snow and George Washington on a horse looking at a few guys freezing in the snow. The much bigger story of that event, told in my book Valley Forge written with Bob Drury, is that it was the turning point of the American Revolution. At no time before or after was the flame of independence flicker so slightly. If George Washington and his ragged, starving, and freezing Continental Army had not survived that horrific winter encampment, Great Britain would have won the war and the United States would have been stillborn.

For the Americans, the Fall 1777 campaign had been one gut punch after another. That September, British troops paraded triumphantly through the streets of Philadelphia, having taken the young country’s capital city and sent into exile the few delegates left in the Continental Congress. Washington’s attempts to retake the city and administer the knockout blow, the cause of liberty so desperately needed, met with failure at the Battles of Brandywine and Germantown. Most humiliating was the Paoli Massacre, in which dozens of American troops were bayoneted by the British as they slept. When Washington’s men staggered into winter quarters at Valley Forge in Pennsylvania on December 19, they were a beaten army that could soon cease to exist.

“As the days dragged on, Washington periodically reined his horses by the road to linger and bear witness as his ghost of an army straggled past. First, the officers on horseback led their stumbling and footsore regiments, then the juddering baggage wagons, and finally the 400 or so ‘camp women’ with their untold children bringing up the rear. These were primal moments. As the commander in chief beheld so many of his soldiers, ‘without Cloathes to cover their makedness—without blankets to lay on—without Shoes,’ Washington later wrote. It must have crossed his mind that the preponderance of his hungry and half-clad were present in a great part out of great loyalty to him. Nor could the irony be lost on him that his days as the leader of this army might well be numbered, through either political perfidy or, as seemed more likely at the moment, the complete dissolution of his vagabond force.”

Once in the encampment, Washington had his men build cabins to shelter them for when the worst of the winter arrived. This was not easily done because many of the men were too weak for the massive construction effort to house 12,000 men and they had few effective tools, like saws and hammers. Day after day they struggled until finally by Christmas most of the cabins were done. Just in time too, because their present for Christmas was a three-day snowstorm.

This had to be the worst holiday of George Washington’s life. In the days leading up to it, he felt abandoned by the Continental Congress, governors of states, and some friends who were beginning to call for his ouster. Most of all, though, he despaired for his men. Though most of his correspondence was dictated to his aides Alexander Hamilton and Tench Tilghman, late one night Washington himself wrote a plea to Henry Laurens, the new president of the undermanned Congress.

Continue reading “George Washington’s Heroism at Valley Forge” on the Unknown History channel at Quick and Dirty Tips. Or listen to the full episode below.