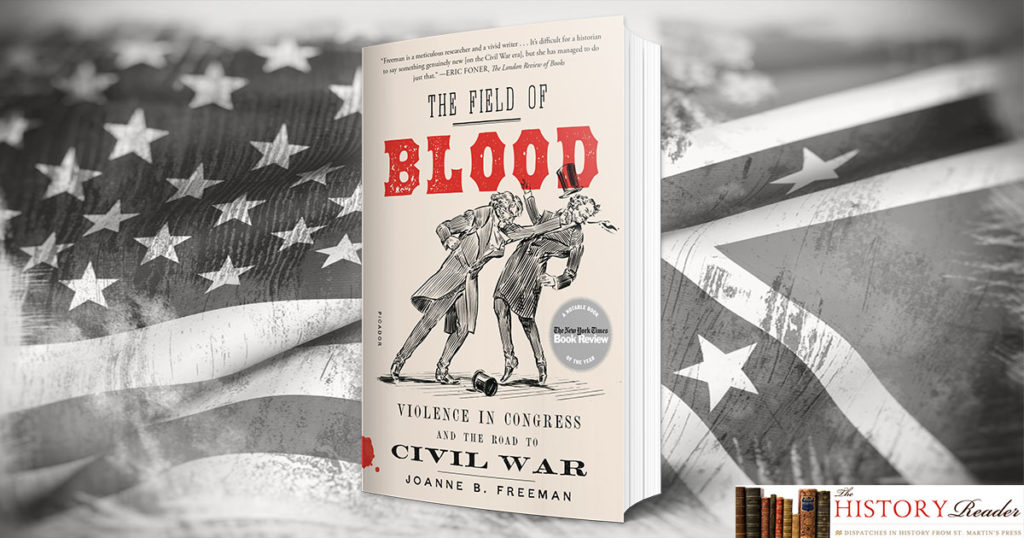

by Joanne B. Freeman

In The Field of Blood, Joanne B. Freeman recovers the long-lost story of physical violence on the floor of the U.S. Congress. In the following excerpt, Freeman shows that the Capitol was rife with conflict in the decades before the Civil War.

In the months before the opening of the Thirty-fourth Congress in December 1855, Americans North, South, and West predicted tough times ahead. A “popular sovereignty” clause in the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which had been passed in May 1854, allowed for settlers in those territories to decide their state’s slavery status for themselves, dividing the nation into two warring factions. Kansas devolved into violent, bloody confrontations over the question, flooding a watchful national audience with graphic images of slave-state and free-state settlers in open combat. The partisan press increased the struggle’s impact by peddling conspiracy theories about a brutal Slave Power or ruthless Northern aggressors trying to seize control of the nation.

The mood in Washington was no better. Well aware that the survival of slavery and the sectional balance of power in the Union were at stake, congressmen were prepared to go to the wall on Kansas’s slavery status. Equally foreboding, a Northern opposition was rising in Congress, challenging the South’s long-held dominance; for decades, a domineering block of pro-slavery congressmen had strategically deployed threats and violence to cow their opponents into compliance. And as if this wasn’t enough, a presidential election would take place the following fall.

In Massachusetts, Henry Wilson, a Know Nothing on his way to becoming a Republican, had dire predictions for the coming session of Congress. (A nativist movement that met in secret, the Know Nothings cohered into the short-lived American Party.) Wilson, a shoemaker, schoolteacher, and newspaper editor who had found his way into politics in the 1840s, had spent a week in June at the American Party’s national convention, bound and determined to “blow the whole thing to hell and damnation” unless the party adopted an anti–Slave Power plank in their platform. When the party refused, Wilson led antislavery Northerners out of the convention, though not without resistance; during one of his speeches, he was threatened by a gun-waving Virginian. “The next Congress will be the most violent one in our history,” Wilson predicted. “[I]f violence and bloodshed come, let us not falter, but do our duty, even if we fall upon the floors of Congress.” By 1855, this once shocking image of bloody combat in the halls of Congress had become commonplace.

At the other end of the Union, South Carolina Democrat Laurence Keitt drew the same conclusions. Keitt, a self-described man of “nervous irritability,” was a fire-eating extremist who was passionately protective of Southern honor. He predicted a “strong struggle” in the pending session, a chance to “marry one’s name to mighty events, to mighty measures,” and to the South’s “immortal future.” Writing from London, Keitt’s friend Ambrose Dudley Mann of Virginia agreed. Because of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the “time has arrived when the South is compelled to measure strength with the North.” If Northerners tried to block slavery from western territories or make Kansas a free state, “it would be the duty of the South to take possession of the Capitol…and expel from it the traitors to the Constitution.”

The same rhetoric pervaded the election for Speaker of the House. When slaveholders began to grill Nathaniel Banks — a Massachusetts Know Nothing on his way to becoming a Republican — about his antislavery views, Preston Brooks of South Carolina took a stand. Resistance to Northern aggression should begin among the South’s appointed leaders in the House, Brooks insisted. “We are standing upon slave territory, surrounded by slave States, and pride, honor, patriotism, all command us, if a battle is to be fought, to fight it here upon this floor.”

Despite such talk, there was no bloodshed during the speakership contest, though there were uproars aplenty and two assaults, both against members of the press. In December, Virginia Democrat William “Extra Billy” Smith—so called because of the extra fees he raked in as a government contractor—assaulted the Evening Star editor William “Dug” Wallach for calling him a Know Nothing in his paper. Wallach routinely carried a “big knife, with which to settle such little controversies,” but the two men did little more than scratch and claw each other, though one of Wallach’s fingers was “catawompously chawed up” by Smith. (Noting the incident, the British foreign minister warned the folks back home that no foreign minister should ever—under any circumstances—go down to the House floor; congressmen were too dangerous.) A few weeks later, when the New-York Tribune denounced Arkansas Democrat Albert Rust for trying to disqualify Banks for the speakership, Rust assaulted the Tribune editor Horace Greeley twice, first punching him in the head on the Capitol grounds, then hitting him with his cane near the National Hotel a short while later. (Rust must have been contemplating a duel because, before striking a blow, he asked Greeley if he was a non-combatant.) Greeley did as many embattled Republicans would do for years to come, portraying himself as a heroic enemy of the Slave Power. “I came here with a clear understanding that it was about an even chance whether I should or should not be allowed to go home alive,” he wrote in the Tribune. Even so, he would stay true to the cause, refusing to run “if ruffians waylay and assail me.”

It took two months and 132 ballots to resolve the election, but ultimately, something remarkable happened: the House elected an antislavery Northern Speaker. Nathaniel Banks’s election was a stunning victory for the nascent Republican Party. When it was announced on the evening of February 2, 1856, the Republican side of the House erupted in a shout of triumph followed by hearty handshakes and heartfelt embraces. The stalwart Republican Joshua Giddings of Ohio, the oldest House member with unbroken service, was given the honor of administering the oath of office. “Our victory is most glorious,” he wrote home the next day. “I have reached the highest point of my ambition…I am satisfied.”

Even in victory, the Republican press predicted trials to come. “There is a North, thank God; and for once it has asserted its right to be a power under the Constitution,” cheered the New York Times. “We shall see whether or not the North can take care of the Union.” Such concern was well founded given the feelings of at least some Southerners, as reflected in a letter to Speaker Banks. Not long after his election, he received a two-page string of insults signed “John Swanson & 40,000 others.” Condemning Banks as “a poor Shit ass trator tory Coward,” Swanson told him to “Quit the US God damn you and your party if you don’t like us.” (And in a sentence that raises interesting questions about Swanson’s image of Hell, he swore that “Hell is full of Such men as You . . . So full that their feet Stick out at the Window.”) Banks must have been amused, or at least struck, because he saved the letter. Doubtless it wasn’t his only piece of hate mail.

Joanne B. Freeman, a professor of history and American studies at Yale University, is a leading authority on early national politics and political culture. The author of the award-winning Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic and editor of The Essential Hamilton and Alexander Hamilton: Writings, she is a cohost of the popular history podcast BackStory.