WCAG Heading

WCAG Heading

WCAG Heading

By David Beasley

Arthur Perry and Arthur Mack, two young black men in Columbus, Georgia, were still riddled with bullet wounds when they stood trial five days after allegedly murdering a white security guard named Charlie R. Helton. An all-white jury deliberated only sixteen minutes before convicting Perry and sentencing him to death in Georgia’s electric chair. Jurors took only five minutes to convict Mack. Both men were scheduled to die September 3, 1937, slightly more than a month after Helton was stabbed to death at the Columbus fairgrounds after an argument with Mack and Perry about beer left over from a company picnic.

The NAACP quickly came to the aid of Mack and Perry, rushing to save their lives. A young NAACP attorney named Thurgood Marshall fired off a telegram to Georgia Governor E. D. Rivers, a Democrat and avid New Dealer.

“Informed that two young Negroes charged with killing white man at Columbus, Georgia July 31st were tried August 5th and sentenced to die September 3rd,” Marshall wrote Rivers. “Both young negroes suffering from gunshot wounds five days after crime and sentencing these men to die less than 33 days after crime obviously not due process of law. Strongly urge you as governor of state of Georgia grant reprieve of sufficient time to permit motion for new trial and investigation.”

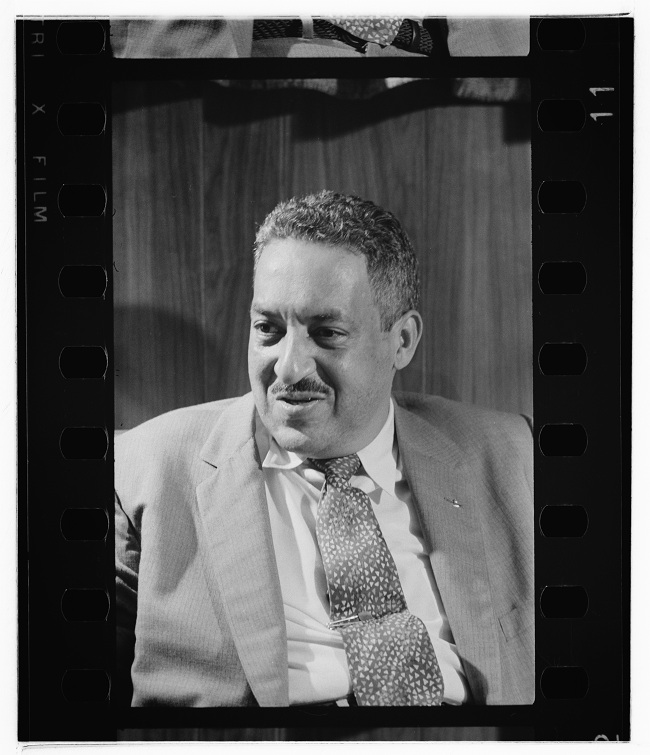

Thurgood Marshall, attorney for the NAACP and later the first African-American U.S. Supreme Court justice, fought to save two Georgia death row inmates, Arthur Perry and Arthur Mack, from the electric chair. [Courtesy Library of Congress]

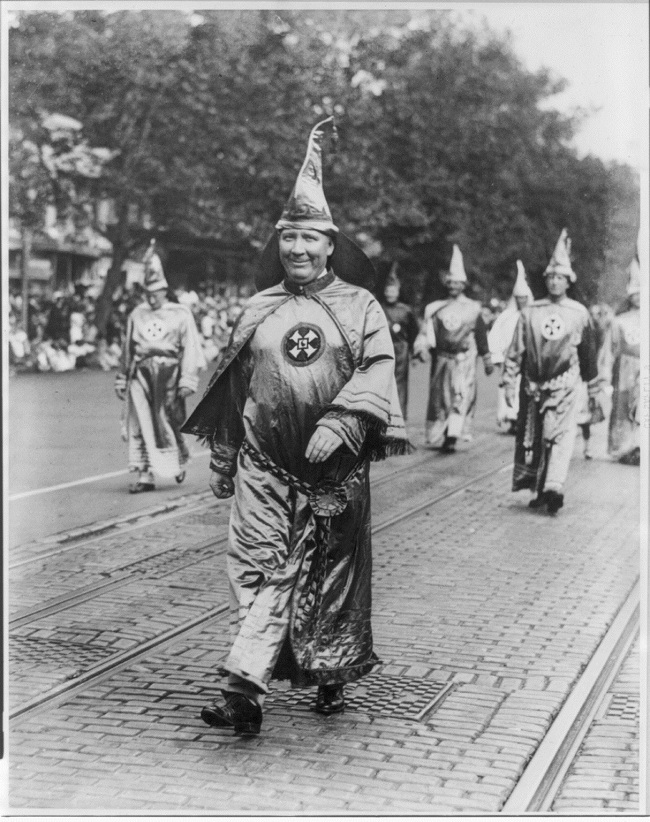

Marshall, later to become the first African-American U.S. Supreme Court justice, likely did not realize who he was dealing with. Although Rivers was a strong supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, he was also a long-time leader in the Ku Klux Klan. While many Southern politicians were Klan members in the 1920s when the organization was booming nationally, Rivers had remained loyal to the organization through the late 1930s. After his election as governor in 1936, Rivers named Hiram Wesley Evans, the Klan’s Imperial Wizard— its national leader— as an honorary member of the governor’s staff. Better yet for Evans, Rivers handed the Klan leader a monopoly on the state’s lucrative asphalt business. Evans had his own asphalt company and also acted as a sales agent for three competing companies. Evans was even allowed to set the prices the companies would charge for asphalt and it was high above the prevailing market rates.

Not surprisingly, Rivers issued a curt reply to Thurgood Marshall’s plea to stop the rapid executions of Mack and Perry in the state’s electric chair.

“Prison commission has no record of matter you mentioned in your wire of yesterday,” Rivers replied to Marshall.

Rivers, the Klansman and governor, was no help, but Marshall was able to retain a white attorney to appeal the Mack and Perry convictions. The two men would not die September 3, but after eventually losing their appeals to the Georgia Supreme Court, would have a new date of death: December 9, 1938.

The smiling, affable Hiram Wesley Evans (above), Imperial Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, leading a parade in Washington D.C., September 13, 1926. [Courtesy Library of Congress]

They would be among seven men—only one of them white—scheduled to die that day, which would mark the largest mass execution in the history of Georgia’s electric chair. As the executions approached, E.D. Rivers would be the only person who could save these seven men.

Rivers has always been remembered primarily as Georgia’s New Deal governor, and he was. His predecessor as governor, Eugene Talmadge, was a suspender-wearing, small government, rural populist who attacked Roosevelt from day one, even going so far as to ridicule the president’s polio paralysis. “The next president who goes into the White House will be a man who knows what it is to work in the sun 14 hours a day,” Talmadge said in 1935. “That man will be able to walk a two-by-four plank, too.”

When Congress approved the Social Security program in 1935, Talmadge made it clear the Georgia would have no part. Allowing blacks to retire at age sixty five would damage the state’s supply of cheap labor, the governor said.

Rivers embraced the New Deal, arguing that it was not charity but reparations for the North’s destruction of the South during the Civil War. With Rivers as governor, older Georgians started getting Social Security checks and they were immensely grateful, even for a $7 monthly payment. In letters, citizens used terms like “divine intervention” for their small checks and even took to writing poetry as they thanked Rivers.

FDR now had a going concern in Georgia for the New Deal. And Rivers pushed FDR’s programs, exceeding even the New Deal goals. He offered free textbooks for school children that resulted in a spike in enrollment, a more educated population. Poor students, no longer embarrassed that they could not afford books, stayed in school longer.

But there was also the sinister side of Rivers—the corrupt Klansman side. There were rumors in 1938 that Roosevelt would endorse Rivers for the U.S. Senate in the “purge primaries” Roosevelt hoped would oust senators who voted against the president’s plan to stack the U.S. Supreme Court. But FDR advisers warned him about Rivers’ Klan connections. The president had, after all, taken heat about his nomination of former Klansman Hugo Black to the U.S. Supreme Court. Rivers skipped the 1938 Senate race entirely, opting instead for a second, two-year term as governor which would prove disastrous.

DAVID BEASLEY is a former editor for the Atlanta Journal Constitution. His latest book is Without Mercy.