by Daniel Blake-Smith

The urban-rural divide throughout American history

Anyone observing America’s ongoing culture wars, especially as they surface in the current presidential election cycle, is forcefully reminded that we are not a country divided by red and blue states; it’s an urban-rural divide that represents the political and cultural fault lines in the nation. The difference is no longer where people live, it’s about how people live: in widely-dispersed, open rural areas with plenty of privacy or in high population density, diverse urban areas where tolerance becomes almost mandatory among its residents.

According to many contemporary political observers, people don’t make cities liberal—cities make people liberal. The gap is so stark that some of America’s bluest cities are located in its reddest states. For example, all of Texas’ major cities—Austin, Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio—voted Democratic in 2012; likewise, other red-state urban areas—Atlanta, Indy, New Orleans, Birmingham, Tucson, Little Rock and Charleston, South Carolina—also voted Democratic.

But how far back does the urban-rural divide go? Before the Civil War, our political and cultural differences fell mostly along state and regional borders. Worldviews and politics followed a mostly north-south direction. For example, the city of Charleston was as staunchly anti-northern as most plantation areas. Economic energies, moral perspectives, and life-ways changed above the Mason-Dixon line, where the North began.

But even in the early 19th century, one can spot the primitive origins of the town-country, urban-rural divide that has become so pervasive in modern America. This was powerfully driven home by the Fletcher family, a clan initially rooted from the colonial era in Massachusetts and Vermont but after the Revolution descendants spread into the South and West. In looking at the lives of the two most prominent brothers who left their Vermont home in the early 1800s (Elijah Fletcher heading South to become a tutor in slave-holding, plantation Virginia, and his younger brother Calvin, who migrated as a teen into Ohio, then settling permanently in Indianapolis) we can glimpse how these New England plowboys—raised on Congregational tenets and antislavery values—developed wildly different social and political values in large part because of where they lived in antebellum America.

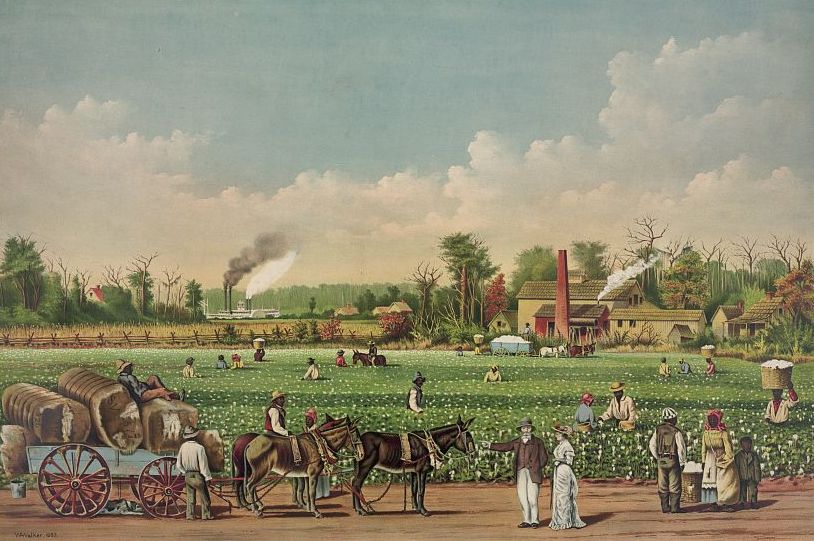

A graduate of the University of Vermont, Elijah left the mountains at age 20 in 1805 intent on becoming a school teacher in the South, a common enough ambition for young educated New England men determined not to become mired back home as impoverished plowboys. He made his way into southwest Virginia near Lynchburg where he eventually took over as a tutor in a plantation neighborhood. After marrying into a prominent slave-holding family, Elijah stunned his entire antislavery family back in Vermont by abandoning the teaching business to become a slave-holding planter himself. “You must not think too badly of slaveholders,” he cautioned his doubtless disapproving father back in Vermont, “for your son is one.” While he owned a political newspaper, The Virginian, Elijah stayed mostly out of politics preferring, like many of his fellow planters, to adopt a detached worldview, focusing on conserving the slave-holding, rural way of life. Reform and change, he came to believe, were disruptive, unwelcome elements in his pastoral world.

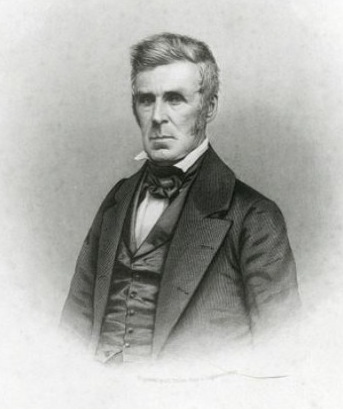

Meanwhile, his younger brother, Calvin, also restless with the dim prospects awaiting farm boys in New England, left home at 17 and journeyed west, landing with a new bride and few prospects in Indianapolis in 1821. Unlike his slave-holding Virginia-based brother Elijah, Calvin, living in a growing urban center amidst other settlers as well as immigrants from Germany and Ireland, along with a sprinkling of free blacks, felt the need to remake the world in his own eyes. And so, like other city dwellers, Calvin found himself increasingly immersed in a precarious, conflicted public world. By the 1840s Calvin had grown into a much more vocal opponent of slavery, even as public opinion, especially in the expanding slave-holding South of his brother Elijah doubled down on their defense of slavery.

When Texas was admitted into the Union in January 1845, Calvin saw the moment as Judgment Day: “I fear it is to hasten the punishment for the national sins & the greatest is negro slavery.” Living in a city where he came to know the prominent minister and activist Henry Ward Beecher (who pastored an Indianapolis Presbyterian Church), Calvin’s antislavery advocacy grew even more forceful. Calvin passionately supported other reforms too, including the temperance movement and the common school reform, first initiated by Horace Mann.

Meanwhile Elijah’s reaction to Calvin’s relentless reform activities was to demean them as “hobbies”—a dismissal that reveals as much about Elijah’s own detached, laissez-faire worldview as it does about Calvin’s reforming zeal. As Elijah explained to his brother, “You are constituted with a zeal for the welfare of mankind that renders you peculiarly fitted for public employment. . . I have not gifts that would make me useful in many things like yourself. I was destined for an unobtrusive, retired life.” But for Calvin, like so many progressive urban dwellers, moral uplift and civic improvement were simply part and parcel of a well-lived life: “I can leave no better inheritance to my children,” he observed, “than a moral, intelligent, religious community & I cannot be an indifferent spectator to these matters & to the interests of this my adopted state.”

When the brothers came together with the larger Fletcher clan at annual reunions back in Ludlow, Vermont, they—perhaps like similar American families affected by the urban-rural divide today—pledged to avoid talking politics and religion. A deeply divisive, bloody civil war, though, dashed all hopes of reconciliation in their America. But their story remains ours today if only in revealing the shaping power of where we live and learn—amongst diverse others in large cities where the watchwords are tolerance and civic improvement or in more private rural enclaves where conserving personal freedom provides the driving force.

Daniel Blake Smith is the author of several books, including OUR FAMILY DREAMS:The Fletchers’ Adventures in Nineteenth Century America, The Shipwreck That Saved Jamestown (Holt), and An American Betrayal (Holt). Formerly a professor of American History at the University of Kentucky, Smith now lives in St. Louis where he works as a screenwriter and author.