by Jefferson Morley

Scorpions’ Dance by Jefferson Morley is the untold story of President Richard Nixon, CIA Director Richard Helms, and their volatile shared secrets that ended a presidency. In the following excerpt from the book, Morley covers Helms’ not entirely truthful testimony to the Senate Watergate Committee.

“The CIA had no involvement in the break-in,” declared the duly sworn witness, Richard Helms, former director of the Central Intelligence Agency, his voice starting to rise. Helms spoke to seven U.S. senators seated at the desks not ten feet in front of him. “No involvement whatever,” Helms emphasized with a broadside of rattling consonants. “And it was my preoccupation, consistently from then to this time, to make this point and to be sure that everybody understands it.”

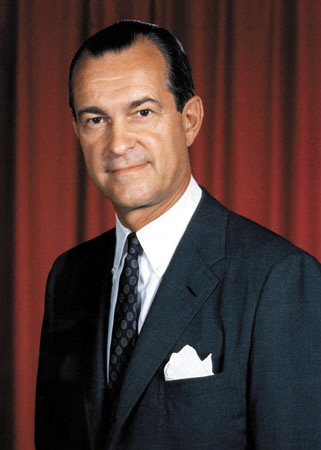

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

Helms, a saturnine scion of Philadelphia’s Main Line, sixty years of age, sat forward at the wooden witness table. His long, slate-gray hair curled over the collar of his silk suit jacket. Filaments of silver glistened on his temples in the glare of white TV lights. His jaw was firm and active. He was surrounded by hundreds of spectators crowded into Room 318 of the Russell Senate Office Building in Washington, D.C. The televised hearings of the Senate Watergate Committee (formally known as the Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities in 1972) were high political theater in America that summer, though not quite the hot ticket they had been a few months before. When the TV camera swung his way, Helms bared his teeth in a grin.

Anticipation accompanied the witness. Richard Helms had served as director of Central Intelligence for almost seven years, from June 1966 until January 1973, when President Richard Nixon named him U.S. ambassador to Iran. He was making his fifth appearance before a congressional committee, but this was his first full public accounting of the Agency’s role in the scandal that had already forced the resignation of Nixon’s chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, and his chief domestic policy adviser, John Ehrlichman. Despite a year of intensive news coverage, first by the Washington Post and then by the rest of the Washington press corps, the role of America’s clandestine service in the Watergate burglary was still murky. CIA directors never testified in open session, much less about a domestic political crime committed by former Agency employees.

The witness caught the crowd by surprise. With one hand, he clasped the microphone at its base. With the other, he chopped the table with his neatly aligned fingers, and his voice rose still further.

“It doesn’t seem to get across very well for some reason but the agency [thump] had nothing [thump] to do [thump] with the Watergate break-in!” he shouted. The murmur of talk in the far reaches of the hearing room was stilled as his words resounded to the high ceiling. No involvement whatever. Helms surveyed the faces around him. “I hope all the newsmen in the room hear me clearly now.”

They did. The CBS Evening News and ABC News both led their coverage of the hearing with footage of Helms’s bravura outburst. A front-page story in the New York Times declared “Helms Says He Resisted Pressure by White House for CIA Cover-up Aid.” The Washington Post lauded his appearance with the headline “Helms Displays His Old Skills as a Diplomat.” Senior Post reporter Lou Cannon wrote that the “quiet and aristocratic professional” who ran the CIA during President Nixon’s first term displayed a “strange sadness” about pressure from the White House. That was a story many people wanted to believe as the Watergate affair consumed Washington: the law-abiding CIA director as an innocent bystander to a lawless president.

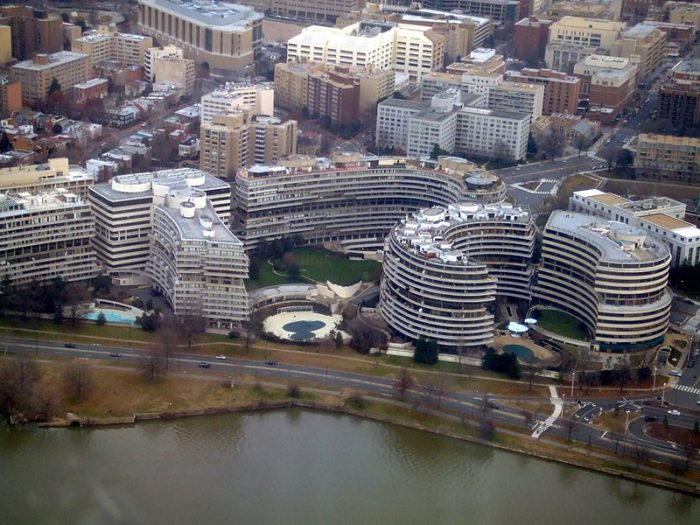

Empirically speaking, Helms’s claim that the Agency had no involvement in the break-in was dubious. Four of the seven men arrested at the Watergate office complex in the early hours of June 17, 1972, had worked on or collaborated with CIA operations to overthrow the government of Cuba. A fifth burglar had held a senior position in the Agency’s internal police force, the Office of Security.

This image is in the public domain via Wikicommons.

“No involvement” implied no connection or association with the burglary. Yet two of the burglars, Howard Hunt and James McCord, had retired from the Agency two years before and gone into business with Helms’s personal blessing and CIA institutional support. The Agency’s statement, reported as fact, that Hunt and McCord “were former employees with whom we have had no dealings since their retirement” was simply false. A month before his arrest, McCord bought electronic gear with Agency help. In retirement Hunt continued to meet with his long-time case officer, Tom Karamessines, the deputy director of operations and one of Helms’s closest confidantes.

A third burglar, Rolando Martínez, was known in the Langley cable traffic as AMSNAP-3. He had worked for the Agency as a full-time boat captain from 1963 to 1971, running hundreds of sabotage, infiltration, and terrorism missions into Cuba. Then he was kept on as an informant.

A fourth burglar, Bernard “Macho” Barker, was a police captain in Havana who had become a CIA source in the 1950s. Known by the code name AMC-LATTER-1, Barker recruited “a number of valuable agents” in Cuba, according to one classified memo. He went on to serve as deputy to Hunt in Operation Zapata, the CIA’s failed attempt to rout Fidel Castro’s socialist government in April 1961. As a prelude to the landing of the CIA-trained brigade at the Bay of Pigs, Hunt and his men planned to assassinate Castro, but Cuban security forces broke up the plot and several of Hunt’s men went to prison.

A fifth burglar, Frank Sturgis, had briefly served in Castro’s government and then joined the exiles in Miami, where he cultivated a reputation for violence. If Helms had checked the file—and he usually did—he knew that Sturgis had once participated in a plot to kill Castro, which the Miami station considered and rejected. No one in the Senate Caucus Room would have guessed that the Watergate crew included three aspiring assassins, and Helms didn’t leave them any wiser.

It was true that the CIA, as an organization, did not select the target for the break-in. But Hunt, the former undercover man working in the Nixon White House, had brought the four Cubans into the operation. Without Hunt there would have been no team of burglars at the Watergate. And unbeknownst to senators and spectators, Hunt was a longtime personal friend of Helms, whom the director had groomed for fame. At the witness table, Helms transmuted tacit involvement into total innocence.

Copyright © 2022 by Jefferson Morley

Jefferson Morley is a journalist and editor who has worked in Washington journalism for over thirty years, fifteen of which were spent as an editor and reporter at The Washington Post. The author of Our Man in Mexico, a biography of the CIA’s Mexico City station chief Winston Scott, Morley has written about intelligence, military, and political subjects for Salon, The Atlantic, and The Intercept, among others. He is the editor of JFK Facts, a blog. He lives in Washington, DC.