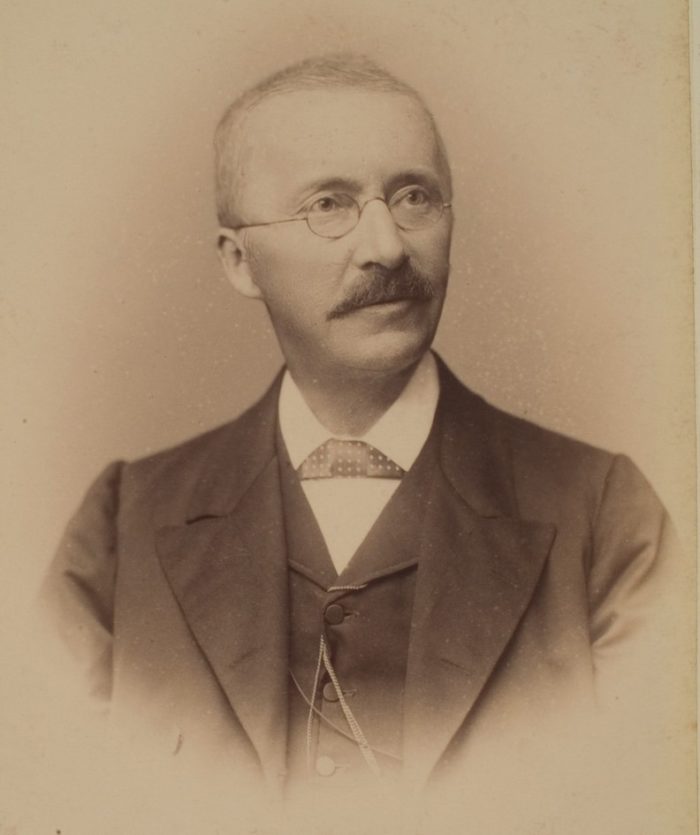

by Edmund Richardson

So you want to find a lost city? Congratulations: you’ve joined an exclusive and perilous club. For hundreds of years, explorers, dreamers, scholars, and fantasists have fanned out across the world, in search of humanity’s lost cities. Their quests have often been dangerous. Some have failed to return. More have failed to find what they sought. But some—a lucky few—have made world-changing discoveries.

[Archaeological Museum of Istanbul, Creative Commons]

Lost cities have fascinated people, ever since Plato first told of Atlantis:

“Now, on the island of Atlantis, there was a mighty and wondrous empire… But then there came earthquakes and floods. And in one terrible day and one terrible night, all the fighting men sank into the bowels of the earth. And the island of Atlantis disappeared into the depths of the sea.”

(Plato, Timaeus)

No one, of course, is going to find Atlantis. Plato’s city was never more than a story. Not all lost cities are real. But some are: buried beneath the earth, hidden in the depths of the sea, or lost in the desert sands. Many have yet to be found: no one knows the location of Itjtawy, once the capital of Egypt, founded in 1971 BC; or Turquoise Mountain, an Afghan city that was a wonder of the world, destroyed by the son of Genghis Khan; or Akkad, the war-capital of the Akkadian Empire, which ruled Mesopotamia over four thousand years ago.

Deciding to find a lost city is the easy part. What happens next—well, that’s where things get complicated.

If you do decide to look for a lost city, here’s what not to do: don’t take the Heinrich Schliemann approach. When Schliemann excavated the ancient city of Troy—the legendary site of Homer’s Iliad—he did so with dynamite. Ancient Troy was a site of many layers: one city built on top of another. Schliemann was sure that the oldest layers were Homer’s city, and blasted straight through anything in his way. Unfortunately, the oldest layers of Troy turned out to be from the early bronze age, a thousand years before any historical Trojan War could have happened. It was not a small error: equivalent to dating the Declaration of Independence to 2776 rather than 1776. Today, Schliemann is celebrated for discovering Homer’s Troy. He actually destroyed it. The layer closest in time to Homer’s city was reduced to dust and rubble.

Don’t take the Arthur Evans approach. Each year, over a million visitors flock to Evans’ greatest discovery, the palace of Knossos in Crete: home of the Minotaur, the fearsome half-man, half-bull of Greek mythology, and the impossible labyrinth of Daedalus. No one tells the tourists that the site is not the work of Daedalus and his artisans, but of Evans and his twentieth-century workmen. Hardly anything is original. Evans and his men, as Evelyn Waugh put it, ‘tempered their zeal for reconstruction with a predilection for covers of Vogue.’ The palace of Minos is a masterpiece of Art Deco and reinforced concrete.

Instead, if you’re looking for a lost city, look where no one else is looking. Listen to the stories no one else is listening to.

In the winter of 1833, a man who called himself Charles Masson wandered the markets of Kabul, Afghanistan, listening. He was looking for a city that had vanished over a thousand years ago: Alexandria Beneath the Mountains.

In 329 BC, Alexander the Great led his army through Afghanistan. His soldiers had traveled further than even the gods of Greece had dared to go. The ends of the earth were at hand. Just outside modern-day Kabul, on the plains of Bagram, Alexander founded a city. He named it for himself: Alexandria. Everyone knows the Alexandria in Egypt, but there were once dozens of Alexandrias scattered across Alexander’s empire. Alexandria Beneath the Mountains flourished for centuries: it was the crossroads of the ancient world, where Greek artists, Chinese traders, and Indian scholars met. Then, it vanished.

In 1833, in the Kabul markets, Masson kept hearing the same story, over and over again: of ancient coins, which no one could read, found in the soil of Bagram. He knew that this could be a sign that something much larger—perhaps even Alexander’s city—was hiding further below the surface of the ground. In the spring of 1833, Masson rode out of Kabul to Bagram, to see if the stories were true.

Masson had no way of knowing it, but he was riding into one of history’s most incredible stories. He would beg by the roadside and take tea with kings. He would travel with holy men and become the master of a hundred disguises. He would see things no westerner had ever seen before, and few have glimpsed since. His quest would take him across snow-covered mountains, into hidden chambers filled with jewels, and to a lost city buried beneath the plains of Afghanistan. He would unearth priceless treasures and witness unspeakable atrocities. He would unravel a language that had been forgotten for over a thousand years. He would be blackmailed and hunted by the most powerful empire on earth. He would be imprisoned for treason and offered his own kingdom. His discoveries—and the lost city of Alexandria Beneath the Mountains—would change the world, in ways he had never imagined.

Edmund Richardson is Professor of Classics at Durham University, UK. He has published Classical Victorians: Scholars, Scoundrels and Generals in Pursuit of Antiquity (2013), and was named one of the BBC/AHRC New Generation Thinkers in 2016.