by Nancy Marie Brown

1. Take off your shirt.

“Berserk” comes from an Old Norse word meaning “bare-shirt” or, maybe, “bear-shirt.” Snorri Sturluson, the 13th-century Icelander who is our main source of Viking lore, isn’t clear (maybe on purpose). In his Edda, Snorri defines berserks as warriors dedicated to the Norse god Odin. Immune to fire and iron, berserks “wore no armor.” They were mad as dogs and strong as bears, he says, but cites a 9th-century poem that dresses them in wolf skins:

“The berserks howled,

battle was on their minds,

the wolf-skins growled

and shook their spears.”

Whatever it really means, berserk is the name that has stuck.

2. Brew your own beer.

Berserks could work themselves into a battle frenzy. Ancient texts say they did so by drinking bear’s blood or by means of ritual dancing. Modern scholars tend to favor magic mushrooms—especially the poisonous fly agaric. But the latest theory is beer.

Don’t be misled by the various modern brews called Berserk Beere. Gruit, or beer made without hops, was current in the Viking Age. Instead, to keep it fresh, brewers added various herbs. Some were psychotropic. Beer made with sweet gale or bog myrtle, for example, has been described as a “stupefying narcotic.” It speeds up the effect of alcohol on the brain, but also makes the heart function more efficiently and the blood to flow faster. Unfortunately, it leaves a “whopping headache,” says Stephen Law, a professor at the University of Central Oklahoma. Here’s a recipe.

3. Bite your shield, not your tongue.

That 9th-century poem is the earliest reference to berserks, though classical sources describe warrior cults in early Germanic societies. In the poem, the berserks “bear bloody shields” and hack through the shields of their enemies, but the act that has come to define “going berserk” is not bearing or hacking, but biting the shield. Take a look at the shield-biting rooks from the famous Lewis chess sets here. That’s the expression to practice in front of your mirror.

Keep in mind that shield-biting is an activity not without some danger. The Saga of Grettir the Strong, written in Iceland in the 1300s, is almost an anti-saga, in which the values of the Viking Age are indicted. Grettir takes no guff from berserks. This one was on horseback: “He began to howl loudly and bit the rim of his shield and pushed the shield all the way into his mouth and snapped at the corner of the shield and carried on furiously.” Grettir ran at him and kicked the shield. It “shot up into the berserk’s mouth and ripped apart his jaws and his jawbone flopped down on his chest.” End of berserk.

4. Laugh in the face of death.

Your fate is already set, the Vikings believed. (For a simple explanation of the Viking belief system, see Karl Siegfried’s Norse Mythology blog. The norns know when and how you will die—you can’t change the cloth they weave. Plus, the only way to reach Valhalla and a glorious afterlife is to die fighting. Die of old age and you’ll never feast in Odin’s hall. No beautiful Valkyries will serve you mead. Instead you’ll spend eternity in damp, dark, dreary Hel, where the plates are named “hunger” and the beds “sickness.” Why not laugh in battle?

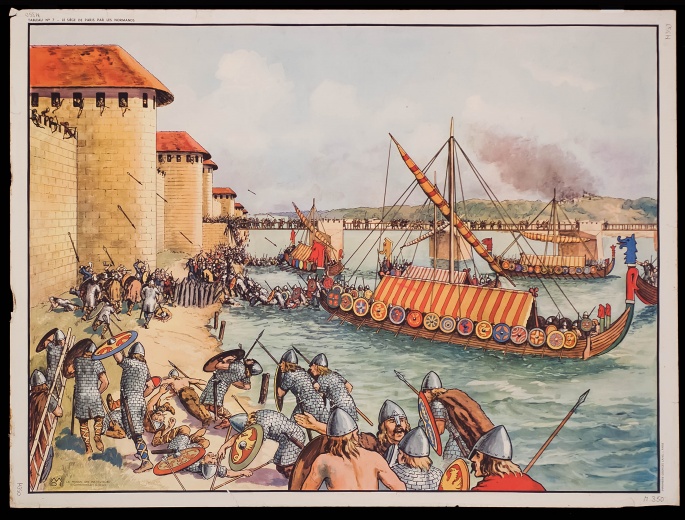

And they did. A monk who witnessed the Viking siege of Paris in 885 described it as “a frenzy beyond compare.” (Yes, this is the battle reenacted in the History Channel’s Vikings TV series. How accurate is the show? According to the monk’s Latin hexameter verse, the Vikings “ransacked and despoiled, massacred, and burned and ravaged,” he wrote. “All bare-armed and bare-backed … with mocking laughter they banged their shields loud with open hands; their throats swelled and strained as they shouted out odious cries.” They had gone berserk.

5. Give up chess.

One early Icelandic saga, the Saga of the Heath-Killings, includes a chess-playing berserk who woos a girl over the game while her father pretends it is just not happening. (Berserks were not good sons-in-law.) Chess and romance were well linked by the time this saga was written, in about 1200. But whether or not chess was known in the north in the Viking Age is still up for debate.

In any case, its tactics are all wrong. Chess is a symmetrical game, with the two sides even and facing each other. Battle in the Viking Age usually wasn’t symmetrical. To learn battle strategy, the better game for a berserk to play is hnefatafl. Here are some of the rules. In this asymmetrical game a single hnefi (the word means “fist”) and his band of berserks fight against a leaderless horde of enemies that outnumbers them two to one. It’s a very Viking scenario. The hnefi wins, not by strength, but by strategy, sacrificing some of his berserks so that he can reach the rim of the board—and victory.

NANCY MARIE BROWN is the author of IVORY VIKINGS: THE MYSTERY OF THE MOST FAMOUS CHESSMEN IN THE WORLD AND THE WOMAN WHO MADE THEM and other highly praised books of nonfiction, including Song of the Vikings. She is fluent in Icelandic, and spends her summers in Iceland. She has deep ties to the Scandinavian cultural institutions in the U.S. Brown lives in East Burke, VT.