by Jonathan D. Quick, MD, with Bronwyn Fryer

The 2020 outbreak of coronavirus has terrified the world–and revealed how unprepared we are for the next outbreak of an infectious disease. In The End of Epidemics, Dr. Jonathan D. Quick examines the eradication of smallpox and devastating effects of influenza, AIDS, SARS, and other viral diseases, proposing a new set of actions to end epidemics before they can begin. Read on for an excerpt.

In the opening scene of the 1993 movie And the Band Played On, a convoy of muddy trucks rolls through a monsoon rain. The mud on the jungle road is several inches deep. The drivers can barely see out the filthy windows. The first truck, emblazoned with the laurel-leaf blue seal of the World Health Organization, pulls up to a field hospital, a long building with a corrugated tin roof. Before exiting the truck, two doctors in blue hospital gowns and gloves strap on gas masks. They walk into the building and look around. The place is deserted and everything looks awry, as if the building has been robbed.

A young boy appears in the doorway. The doctors take off their masks and smile at him. “Where’s the doctor in charge?” they ask in a friendly way.

“Doctor,” says the boy. “Yes. I take you.”

They follow the boy from the building. The boy points to a row of corpses lying on the ground.

“Doctor,” the boy says, pointing to the dead white man.

One of the visitors hears the sound of groaning and follows it into a hut where a woman lies dying on the floor. When he comes closer, she grabs his arm, babbling, and vomits blood onto his hand.

Later, the two doctors burn all the corpses. As one of them stares at the flames, words appear on the screen: “The Ebola fever outbreak was contained before it could reach the outside world. It was not AIDS. But it was a warning of things to come.”

And the Band Played On was based on a book of the same name by San Francisco Chronicle reporter Randy Shilts. The irony in the opening scene is deep from a contemporary perspective—the warning on the screen pertained not just to AIDS but to the future Ebola epidemic that would devastate West Africa in 2014. Both the book and the film offer brutal portraits of confusion, fear, denial, and indifference in the face of the catastrophic AIDS epidemic that resulted in millions of needless deaths. The book was published in 1987, seven years after AIDS began decimating gay communities in the United States. The movie came out a decade before Ebola’s next terrible version reached the outside world.

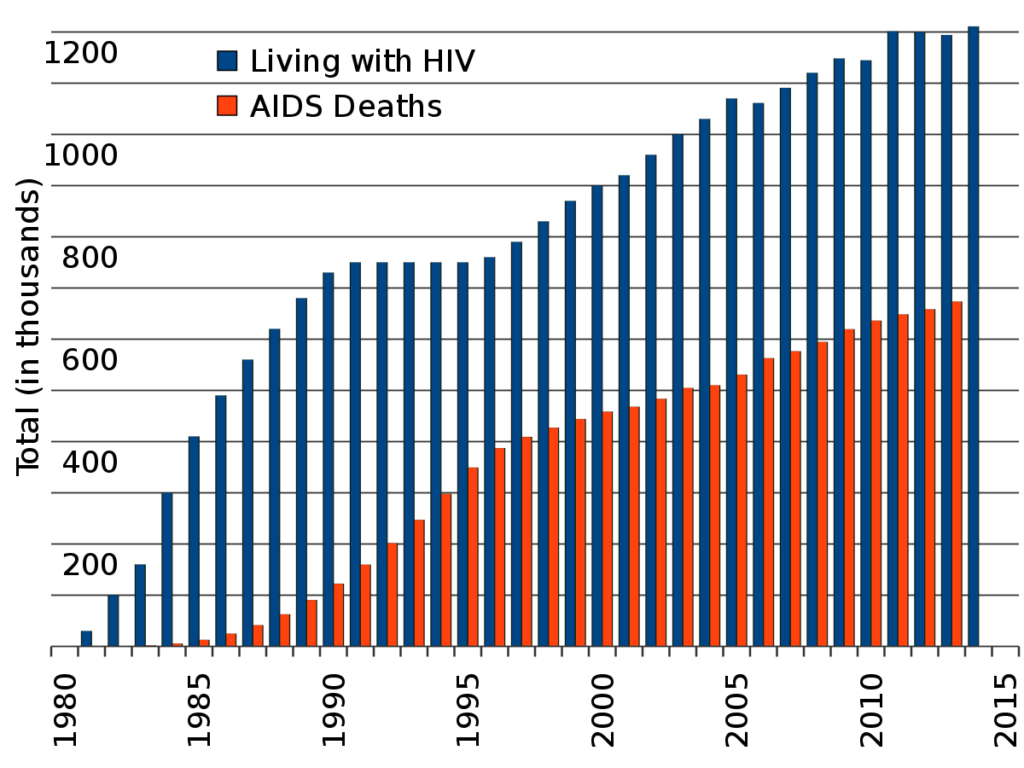

Like Ebola, HIV also sprang from intimate contact with a jungle animal. Scientists think it jumped from chimpanzees to humans in the early part of the twentieth century, most likely when a hunter in Cameroon slaughtered a chimp for food. While the hunter was wielding his knife, he probably cut his own skin and the animal’s blood got into the hunter’s bloodstream. The hunter infected his wife and family. The virus he contracted was not just the most deadly new virus of the twentieth century, it was also the first new human pandemic pathogen to appear in at least a thousand years. It ranks with a small number of diseases that are so virulent that, left untreated, they are 100 percent fatal. By 2015, AIDS had infected nearly 80 million people worldwide and killed nearly 40 million of them, leaving waves of survivors and orphans in its wake.

Was the AIDS epidemic inevitable? Some AIDS experts (and a number of my colleagues) would say yes, because the HIV virus, all by itself, is one of the most awesome viral geniuses ever observed. It’s highly adept at evading the body’s immune system, a secretive characteristic that has completely stymied development of an AIDS vaccine for more than 30 years. Unlike smallpox or Ebola, whose symptoms become clear in pretty short order, HIV takes a long time to turn into AIDS. Symptoms typically begin with a mild fever and sore throat that start within weeks of becoming infected and quickly pass. The virus hides out in the bloodstream, doing its dirty work, for more than a decade before clinical signs of AIDS appear. Throughout this period, the infected individual can transmit the virus through unprotected sex, dirty needles, and via blood from a pregnant mother to a fetus. When it turns into full-blown AIDS, it destroys the body’s immune system, rendering virtually every part of the body vulnerable to opportunistic cancers or infections.

This file is made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

In the 1970s, many years after the first human infection in Africa, AIDS first began sickening San Francisco’s gay men. The virus wasn’t discovered until the early 1980s, when a cluster of men in San Francisco suddenly came down with a variety of strange symptoms including swollen lymph nodes, rashes, sores, skin cancer, pneumonia, and wasting fevers; the disease was initially called GRID (Gay Related Immune Deficiency). By 1981, it was clear that one of the most mysterious and awful diseases the international medical community had ever known had been unleashed, and it had rolled a gravestone over what had been a rainbow-happy celebration of sexual freedom.

The story of AIDS is long, complex, and unutterably tragic. AIDS spread because of three tenaciously intractable human behaviors: sex, injectable drugs, and especially the politics and ideology that took precedence over public health (a topic I will explore in more depth in a later chapter). For public health professionals, AIDS has been a long war on both the individual and collective fronts. As Michael Hobbes of the New Republic observed, “Just as the AIDS virus seems almost designed to perfectly exploit the weaknesses of the human immune system, treating it seems designed to exploit the weaknesses of our national health systems.”

From the earliest days of the epidemic, conservatives in the U.S. demonized and stigmatized those with AIDS, resisting preventive measures such as condom use and clean-needle programs. Even today, needle exchanges are banned in almost every state in the southern U.S., where the AIDS epidemic is now concentrated and HIV infection rates are ten times higher than in other parts of the country. At the same time, in the early years of the epidemic, liberals and gays also fueled the epidemic by opposing proven public-health practices such as testing, case finding, and telling public-health authorities the identities of their partners. In contrast to the U.S. dynamics, Australia’s conservative government put science first and quickly enacted sound public health practices.

Copyright © 2020 by Jonathan D. Quick, MD, and Management Sciences for Health, Inc.

Dr. Jonathan D. Quick is Senior Fellow and former president and CEO at Management Sciences for Health in Boston. He is an instructor of medicine at the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Chair of the Global Health Council. He has worked in more than seventy countries. He lives in Massachusetts.

Bronwyn Fryer is a collaborative writer and a former senior editor for the Harvard Business Review. She lives in Montpelier, Vermont.