Cold Crematorium is the first English language edition of a lost memoir by Holocaust survivor József Debreczeni, offering a shocking and deeply moving perspective on life within the camps. Read an excerpt below, or scroll to the bottom to listen to the same excerpt from the audiobook edition.

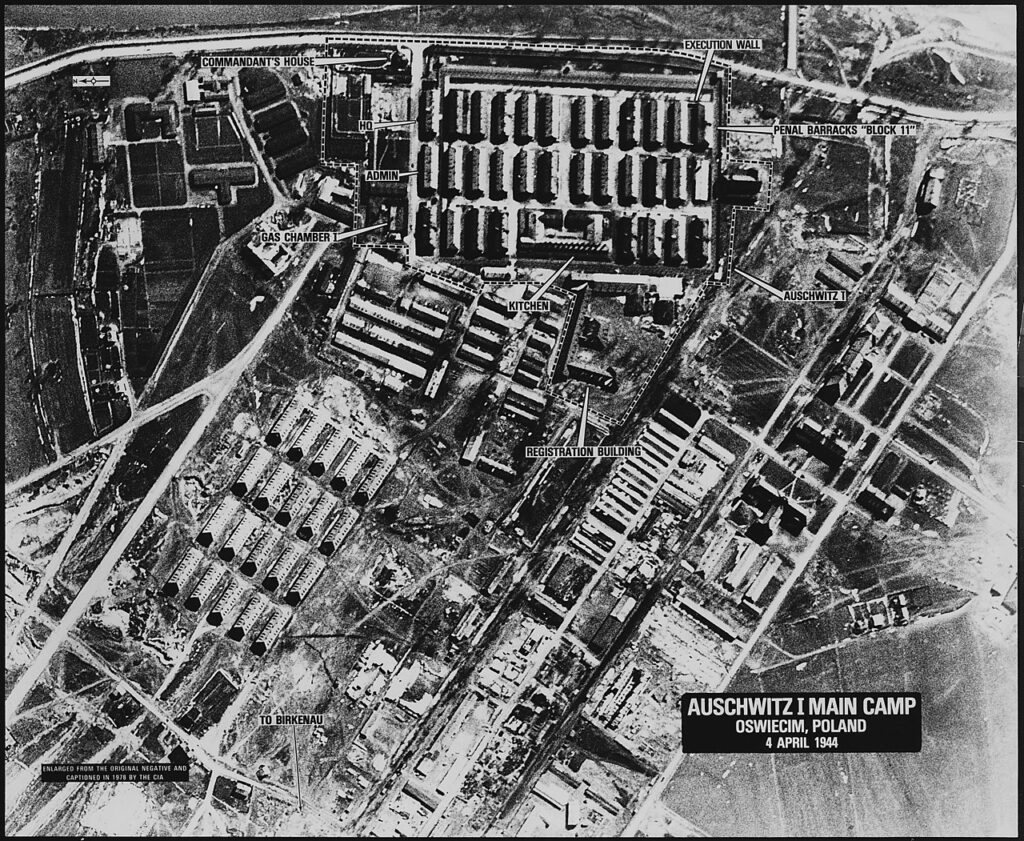

Auschwitz…

A gaunt SS officer approaches. One of the grass-green guards stands bolt upright at attention and barks out a report. The officer nods, says something, and at once the command rings out:

“Get out, with bags too! Everyone line up in front of their cars. Los [Come on]!”

The breeze goes right through me—it’s been a while since I’ve felt one—and I squint in the morning light. The warm short lambskin jacket I’m wearing has been with me through four different labor camps. It’s dependable, to be sure, and yet here I shudder all the same. Perhaps it’s not the air that does this to me but waiting for the unknown. Beside me, Márkus, a man of means from Subotica, chews away stubbornly on some bread crust. He’s also run out of cigars. The last pungent Virginia died out between those ever-grumbling lips before we got as far as Nové Zámky. Who knows what he was thinking? This man who for fifty years kept chasing a mirage that can be expressed in numbers: money. And now, as if he were a stray bug, the guard swatted him off the bag of treasures he had been painstakingly weaving for a long time.

Meanwhile the grass-green guards, with the help of some paint-splotched figures, throw the motionless from the cars. The veteran häftlinge work indifferently and adeptly. They fling the bodies onto handcarts—there may be living among those bodies—and then wordlessly set their shoulders to the handles.

A new command: “Bags are to be left in front of the cars! Line up in rows of five!”

Again, the marching column we had back in Topola has taken shape, but now pared down quite a bit: there are perhaps one thousand or twelve hundred people here still able to stand on their feet.

We cast agonizing glances toward our bags. If we can’t take the stuff with us, the chance of quick annihilation is even greater. If need be—so we had thought—we could trade in our blankets, warm clothes, and brand-new hobnail boots for food.

The procession began reluctantly, although a bit of encouraging news was already making the rounds, but who knows how it began:

“They’re bringing the luggage on a truck behind us.”

After a few hundred steps came the command to stop. A big, almost perfectly square space. Just as large as that major intersection, Oktogon, along the Grand Boulevard back in Budapest. Barracks with chimneys spewing out smoke. To the right, a yellow-and-black crossing gate closes off a well-maintained, steep road. A watchtower. A machine-pistol-toting sentry was stomping back and forth a few steps away from the wooden structure, and machine guns were yawning our way from the tower’s loopholes. Fifteen or twenty trucks were all around us, with armed SS soldiers and drivers beside them. The grass-green guards who’d accompanied us from back home had vanished. On the square, in gray uniforms, SS lads, junior officers, and senior officers—the “gray ones,” as I came to think of them—were strutting about.

First, the women were commanded to separate from the rest of us. They stagger and stumble along, one behind the other, numb with fear. Hundreds of people, with watery eyes, watch their wives, mothers, and daughters now fade into the distance. Mothers and daughters spasmodically clasp each other’s hands as girlfriends do the same. The sparse, silvery hair of trembling old women sparkles in the sun. Mothers with babies shrieking in terror are lulling them or deliriously squeezing them to their breasts. In a sprawling, stretched-out column the women and girls now disappear forever. Moments later the barracks envelop them, but the crying of children can be heard for quite a while.

A group of four men approaches us: two officers, a tall one with gold-framed glasses and carrying a paper form, and another, toting a briefcase; and two storm troopers with icy expressions. They stop, step apart, with two on each side facing each other. We must pass between them in a line down this narrow corridor they’ve fashioned. The man with the form in his hand glances at everyone and gives a wave of his hand. Right or left. The other three drive the victims accordingly in the direction indicated.

Right or left. To a life of slavery or to death in the gas chamber.

Those who’ve made it home know what it meant if someone went left. But, then, we didn’t know yet. The decisive moment slunk away, unnoticed, amid the others.

The gray-haired, the emaciated, the nearsighted, and the lame mostly go to the left. So that’s the “medical exam.” In a half hour two almost identically long lines of people, five to a row, form on the right and the left. The four Germans consult briefly, whereupon one of them steps between the two groups.

“There will now be a ten-kilometer march uphill to the camp. You”—and he points to the left—“older and weaker ones will go by truck, the others on foot. Anyone among those on the right who doesn’t feel strong enough to walk can step over to the left.”

Long, heavy moments of silence. The condemned and their executioners stare at each other. The announcement, issued in such a detached, natural-sounding voice, doesn’t spark a bit of suspicion. Only a few of us are flummoxed by the generosity. This is not the Nazis’ style. Many prepare to go all the same. Even I make an involuntary movement. That’s when one of the carts carrying the dead turns closer to us. It rattles past between the two columns a few steps away. The häftling beside the shoulder bar does not look at us, but I can hear his subdued voice:

“Hier blieben! Nur zu Fuss! Nur zu Fuss! [Stay here! Only on foot! Only on foot!]”

He says it several times, but few of us hear this stranger’s lifesaving warning. I decide. I’m scared of the journey on foot, and yet I stay. It’s more that I obey some instinct that suddenly flares up in me rather than the comrade pulling the handcart. I grab the arm of my neighbor, Pista Frank.

“Don’t go over,” I whisper.

Nervously he tears himself from my grip and heads off. Others too. The line thins out noticeably. The gray ones smile slyly, whisper among themselves, point toward us. Once those who’ve opted to go have gone, our group is surrounded by two platoons holding bayonets up high. We’re off.

Those on the left are still standing there. We pass by them closely indeed. There is Horovitz, the sickly old photographer; Pongrác, the wheat farmer; and Master Lefkovits, whose prestigious long-standing men’s clothing store on Main Street had supplied so many of the fancy silk neckties and shirts of my twenties youth; Weisz, the lame bookseller; Porzács, the morbidly obese jazz pianist, who in Subotica’s most fashionable café popularized the latest hits with boundless ambition if with deficient technical aptitude. There, with the corners of his mouth turned down, looking withered, and with six days of white stubble, was Waldmann, who taught Hungarian and German literature in the “Royal Hungarian” high school in my hometown. Hertelendi, the half-witted midget, Samu, whom everyone called a war simpleton, though no one knew why. Here was Kardos, the lawyer from Szeged with heart trouble. He was my age, and we’d met four times already when forced into labor service. A notorious slacker, he always managed to dodge the work. Most recently this was our jocular farewell, at the camp in Hódmezővásárhely: “Until we don’t see each other again at labor service.” Now here he was, standing in that outrageous yellow corduroy “enlistment outfit” of his, as he called it. This is what he always wore; he’d gotten it on even for the most recent enlistment. His eyes sparkle snidely from behind his horn-rimmed glasses as he stares at our group. He clearly believes that even now he chose the better option. Why, he won’t even be walking the ten kilometers!

And here are the rest of us. I glance at faces familiar and unfamiliar. Acquaintances and semi-acquaintances—ten, one hundred, five hundred.… The engines of the waiting trucks have already started up. The crossing gate, painted red, white, and black, rises before us, and we turn down the sloping asphalt road, which is lined with barracks. The watchtower’s machine guns turn slowly toward us.

As for them, those on the left, no one saw them ever again.

Click below to listen to the excerpt:

MacmillanAudio · Cold Crematorium by József Debreczeni, translated by Paul Olchváry, History Reader audiobook excerpt

Copyright © 2023 by the Estate of József Debreczeni.

József Debreczeni was a Hungarian-language novelist, poet, and journalist who spent most of his life in Yugoslavia. He was an editor of the Hungarian daily Napló and of Űnnep in Budapest, from which he was dismissed due to anti-Jewish legislation. On May 1, 1944, he was deported to Auschwitz after three years as a forced laborer. He was later a contributor to the Hungarian media in the Yugoslav region of Vojvodina, as well as leading Belgrade newspapers. He was awarded the Híd Prize, the highest distinction in Hungarian literature in the former Yugoslavia.