dd

by Buddy Levy

While I was researching Empire of Ice and Stone, I was deeply moved by the courage and skill of the Inuit (native Alaskan) members of the Canadian Arctic Expedition of 1913 and their crucial contributions during the year-long ordeal. For all the blunders and poor decisions made by expedition leader Vilhjalmur Stefansson, hiring a group of Inuit hunters and a seamstress turned out to be one of the smartest things he did. That and managing to get Arctic legend and master mariner Bob Bartlett to captain the Karluk.

In early August 1913, Captain Bartlett was weaving the flagship Karluk through rough, ice-choked seas near Pt. Barrow, Alaska, en route to an intended rendezvous at Hershel Island (just north of the Canadian Yukon) with three other ships of the expedition. Bartlett anchored a mile off the shore of Cape Smyth and waited for Stefansson, who had gone ashore to procure more sled dogs and provisions, including essential skins for Arctic clothing. Before long the scientists and crew of the Karluk heard barking dogs and went to the rail to see Stefansson and two Inuit men driving three large dog teams.

Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada.

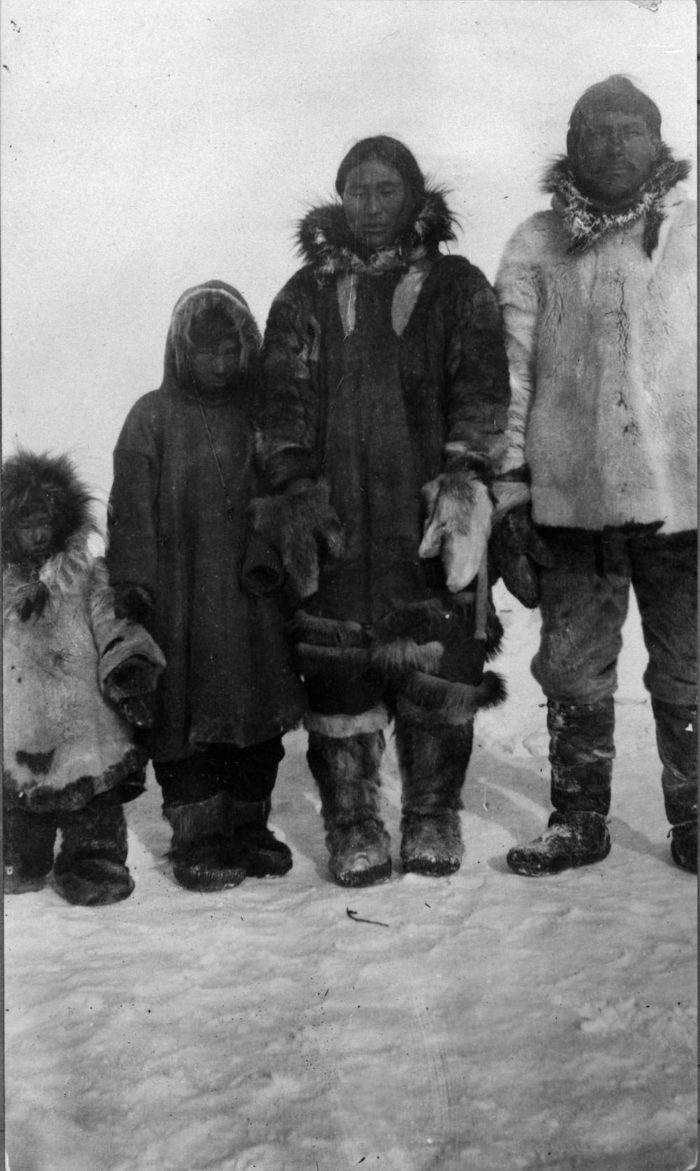

When they boarded the ship, Stefansson informed Captain Bartlett that he’d hired an Inuit family who would be coming with them. The husband, named Kuraluk, had a reputation as a fine hunter; his wife, Kiruk (nicknamed “Auntie” by the crew) was a skilled seamstress. They’d brought along—as was customary—their children, two young daughters, eight-year-old Qagguluk (“Helen”) and three-year-old Mugpi (“Ruth”). A few hours later, another young Inuit man named Kataktovik arrived. He was just nineteen but was known to be a superb hunter and igloo builder. Both men were also expert sled dog drivers.

The skills of these native Alaskans were put on display immediately and ultimately saved many lives. Auntie began sewing coats, pants, and boots needed to survive on sea ice. The clothing made from furs, hides, seal skins, and intestines was superior to the woolen garments often used by British, American, and Canadian arctic expeditions because wet wool was difficult to dry and would freeze quickly, leading to hypothermia and even death. The traditional Arctic garments Auntie sewed were ideally suited to the harsh Arctic environment, being pliable, durable, breathable, windproof, and waterproof. Auntie also taught the crew and scientists how to line the bottom of the boots with grasses and lichens she’d brought from shore to soak up moisture and keep the soles of their feet from becoming frostbitten.

Auntie’s process for preparing caribou and bear hides was laborious and time-consuming. The skins had to be washed and scraped to remove any fat, tissue, meat, oil, or blood, then dried for 10-12 hours. Once dried, Auntie and her girls Helen and Mugpi softened the hides to make them supple enough to sew and wear. They folded and stomped on the dried hides, and even chewed them, because human saliva softened the skins by breaking down the tissue. For extra waterproofing, Auntie sewed the dried intestines of seals and walruses into coats and added the fur of polar bears or foxes for hoods.

Courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

Kuraluk and Kataktovik started hunting seals immediately since the expedition required fresh meat to prevent scurvy. Whenever the Karluk became stuck in ice, the two Inuit hunters would disembark and head to open pools, where they’d wait silently for hours until a seal surfaced and they got a shot. But shooting a seal did not guarantee its procurement. They might sink, or float, but they still had to be brought in. The regional native peoples had devised an ingenious tool for this purpose called a “manak.” At the end of a long piece of line, they attached a five-to-six-pound lead weight, and a foot or two beyond the weight was tethered a four-clawed grappling hook. As the seal floated, the hunter would coil the line like a lasso and, swinging the hook around like a cowpoke roping horses, throw the hook some feet beyond the seal, then reel in the line, snagging the carcass and dragging it to the edge of the ice where they could reach down and grab it. They butchered the seals with remarkable speed and efficiency. Most of the crew found the meat extremely tasty, despite its dark color and strong, fishy smell. The ship’s cook began serving seal once a week as a treat, using the liver for what he called “seal steak and kidney pie.”

The young girls Helen and Mugpi contributed daily, not only by sewing but also by employing innovative hunting techniques while stranded on an island above northern Siberia. By this time many of those marooned were starving to death, and any food was lifesaving. While the men hunted seals and walruses, ducks and shorebirds, Helen devised a clever technique to procure seagulls. She fastened a chunk of seal blubber to a feather quill, to which she attached a length of twine. She’d creep close to a gull, toss the piece of blubber a few yards from it, and when the gull came over to eat the blubber, the quill would serve as a hook, lodging in the bird’s mouth or gullet and Helen would reel the bird in as if she’d caught a fish. In this way she was able to catch a few gulls a day, providing much-needed meat.

Around the same time (September 1914), Auntie and the girls began jigging for polar cod, a pan-sized Arctic species that can survive in icy, sub-zero water because it produces a glycoprotein that becomes an antifreeze in its blood. Auntie had spotted schools of these fish, which were about fifteen inches long, swimming fast through shallow water in tidal cracks in the beach ice. She made a crude jig by bending a sewing pin and piercing it through one end of a long length of sinew. She and the girls would hover motionless at the edge of the tidal crack, lowering their jigs down into the water. When the fish swam by, they’d jerk hard upward, skewering the tomcod on the pin and yanking them out of the water and onto the beach ice. It was slow and tedious fishing, but they caught plenty. The fish thwarted starvation and bolstered morale.

When it became clear that the group of a dozen members would not survive another winter on tomcod and seagulls, Kuraluk agreed to build a kayak to hunt the icy waters offshore for seals and maybe walruses. Kuraluk was at first reluctant, and his reservations were reasonable. It was dangerous hunting seals or walruses in a small, one-person kayak. Capsizing in that icy water meant certain death. Enormous walruses, weighing up to 3000 pounds, were terrifying. Their huge white ivory tusks—protruding two feet long straight out of their mouths like spears—could pierce his skin kayak and sink him in an instant. Kuraluk knew that he was the only one among them who was experienced using a kayak, so it was his life that would be at risk. But since he alone possessed the necessary skill, Kuraluk agreed to build one.

Kuraluk found a couple of logs long enough to cut lengths for the frame and dragged these near the tents where he could sit on a stump and work. For tools, he used a skinning knife, a snow knife, an axe, and a hatchet. Kuraluk used the hatchet blade as an adze to rough out the side rails and rib frames from the logs. The construction was a slow, painstaking process as he lashed the separate pieces of the framework together with sealskin thongs. He carved and whittled a double-bladed paddle out of a washed-up plank of lumber, and two weeks after starting the task, he brought the frame inside his family’s tent to dry. Auntie took measurements and cut lengths of sealskin and sewed these taut around the frame, and the kayak was complete. Everyone was impressed. “When finished,” one member’s diary reported, “It looked as if it had been made by some expert boat builder, with modern tools and convenience…instead of with only a hatchet and a knife.”

And then, almost as if on cue, the shipwreck survivors could hear a distinct barking and bellowing, the lion-like roars of walruses in the bay. Kuraluk crept down to the water and eased the boat into a small open lead, his eyes always on the massive brown creatures lazing on an ice floe a few hundred yards offshore. His heart pounded and his hands were clammy inside his mittens, but he grabbed the two-bladed paddle in one hand, his rifle in the other, and slid into the boat. Winds were light and favorable, and he could see an open lane skirting around the floe on which the pod of five enormous animals was sunning. If he took his time and didn’t spook them, he might be able to paddle into position for a shot.

Now, everyone’s hopes for survival depended on his courage and skill…

Originally published on Buddy Levy’s Adventure History.

Buddy Levy is the author of more than half a dozen books, including Labyrinth of Ice: The Triumphant and Tragic Greely Polar Expedition; Conquistador: Hernán Cortés, King Montezuma, and the Last Stand of the Aztecs; River of Darkness: Francisco Orellana’s Voyage of Death and Discovery Down the Amazon. He is co-author of No Barriers: A Blind Man’s Journey to Kayak the Grand Canyon and Geronimo: Leadership Strategies of an American Warrior. His books have been published in eight languages. He lives in Idaho.