By Giles Milton

A change in the cloud pattern brought the first suggestion of land. Next came the seabirds and leaves in the water. And finally (and to a resounding cheer) the faint smudge of coastline would be sighted – grey at first, and then mauve, before it darkened and sharpened into a brilliant tropical green.

The hardy Jacobean adventurers who traveled to the fabled East Indies rarely spent less than a year at sea before arriving at their destination. Most suffered appalling deprivations while on route to Java. Scurvy, dysentery and tropical storms wreaked a terrible toll on men already weakened by months of eating salt pork and hard tack biscuits.

They’d never forget their arrival in the tropics and would often set quill to paper, writing up their experiences in scratchy, spidery handwriting. Hardy adventurers like John Jourdain and Edmund Scott left such detailed accounts (these days housed in London’s India Office library) that any enterprising historian could write an encyclopedic account of life in the Javanese port of Bantam – the first stop for most voyages orchestrated by the East India Company.

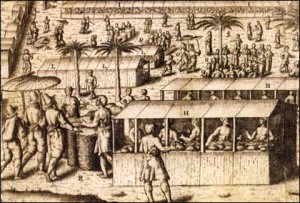

Bantam was the largest commercial entrepôt in Java and the dominant marketplace in the East Indies. In the early 1600s, it was the place to buy the rarest and most costly of spices – cloves, cinnamon and nutmeg.

But the English sea-dogs who pitched up here quickly discovered that Bantam’s gilded promises were deceptive. The city was surrounded by oozing mudflats and malarial marshland and its drinking water was seriously contaminated. One English captain, Nicholas Downton, labelled the city ‘that stinking stew’. Another said that ‘Bantam is not a place to recover men that are sick, but rather to kill men that come thither in health.’

This was certainly the case for the great fleet commanded by Sir Henry Middleton, which arrived here in December 1612 after a nightmarish, thirty-two month voyage. Dozens of Middleton’s sickly crew succumbed to ‘the blody fluxe’ – dysentery – and died within days of landing. By the time the next English ship staggered into port, just four men remained on their feet. Even these hardy survivors looked ‘like ghosts or men frighted.’

Back in London, the directors of the East India Company were woefully ignorant of the perils of life in Bantam. They took the decision to establish a trading post in the city, one that was to be permanently manned by a dozen adventurers.

One of them was Edmund Scott, whose daily journal charts the full horror of life in this rotting, disease-ridden port. Scott’s men lived in constant fear of attack from rival traders and scarcely a day passed without them being assaulted by bandits. For two years they cowered inside their flimsy wooden warehouse, surrounded by its palisade of sharpened stakes. They were so haunted by the fear of murder that ‘our men in their sleepe would dreame that they were pursuing the Javans and suddainely would leape out of their beddes and ketch [grab] their weapons.’

The greatest risk to their livelihood came from fire: local spice-dealers found arson a conveniently destructive method for dealing with rivals. The wood-built English warehouse was particularly vulnerable.

‘Oh this worde fire!’ wrote Scott in his quirky Jacobean English. ‘Had it been spoken neere mee, either in English, Mallayes, Javanese or Chynese, although I had been sound asleepe, yet I should have leaped out of my bedde.’

On one notable occasion, Scott managed to catch a would-be arsonist. Instead of prosecuting the man in the local courthouse, he chose a more direct form of punishment.

‘First I caused him to be burned under the nayles of his thumbes, fingers and toes, with sharpe hotte iron and the nayles to be torn off… then we burned him quite thorow the hands and with rasps of iron tore out the flesh and sinews. After that I caused them to knocke the edges of his shinne bones with hotte searing irons.’

The battered man still refused to repent, so Scott tied him to a stake and had his men slowly shoot him. ‘The first shott carried away a peece of his arme bone, and all the next shot struck him thorough the breast.’ By the time they had finished, ‘they shot him almost to peeces.’

Edmund Scott’s testimony is uncompromisingly frank, revealing that horrific violence was a daily reality of life in Bantam. He offers no excuses and no apologies; indeed, it is the matter-of-fact tone of his account that makes it so disturbing.

While it does not make for comfortable reading, it allows us a unique peek into the hellish lives of England’s brutalized merchant adventurers.

Giles Milton is a writer and journalist. He has contributed articles to most of the British national newspapers as well as many foreign publications, and specializes in the history of nutmeg, travel and exploration. In the course of his researches, he has traveled extensively in Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas. He has written several books of nonfiction, including the bestselling Nathaniel’s Nutmeg: or, The True and Incredible Adventures of the Spice Trader Who Changed the Course of History, and has been translated into fifteen languages worldwide. He is also the author of the novel Edward Trencom’s Nose.